Wisconsin mom exposes painful reality of abortion laws after tragic pregnancy loss

Synopsis

Abortion may be legal in Wisconsin, but the hurdles still involved forced mom Gracie Ladd, 33, to flee the state anyway. She shared her story with UpNorthNews writer Bonnie Fuller.

The first clue that something was wrong happened about halfway through my 18-week anatomy scan for our second baby.

My husband, Brian, was with me, and my pregnancy had been going fine. All the earlier ultrasounds were normal and the genetic screening had also come back normal.

We had recently done a sneak peek gender reveal, and I was pretty excited to find out we were having another boy. Our first son, Austin, was 3, and I’ve loved being a boy mom.

We decided to call our new baby Connor Miles. We chose Miles for Connor’s middle name because it’s Brian’s mom’s maiden name. That way, we could keep her name in the family.

At first, everything at the anatomy scan seemed routine. The technician was working, and about halfway through she asked me to go to the bathroom and empty my bladder.

When I came back, she said, “I’m going to take you to a different room because the doctor was watching the scans and wants to talk to you about them.”

That was my red flag that something was wrong. Because I had been pregnant before, I knew that having the doctor come in midway through the anatomy scan doesn’t usually happen.

I felt my stomach drop.

Brian didn’t realize anything was wrong until I told him.

He’s a quiet, reserved person, but when I warned him that this wasn’t normal, I could feel his energy shift, just like mine.

Brian and I have been married for six years. We met at the University of Wisconsin-Madison when we both worked at a well-known campus restaurant, called Der Rathskeller.

We dated all through college, and got married in 2019 in Madison. Now, we live in a suburb outside the city.

We always knew we wanted two kids. But before I got pregnant with our first, I wanted to fulfill a bucket list item—compete in an Ironman Triathlon.

That meant swimming 2.4 miles, biking 112 miles, and running a full marathon of 26.2 miles. I’d always been a runner and was working on doing a marathon in every state when a friend asked me to do the Ironman with her.

It was an amazing experience and a wonderful community of athletes.

Shortly after I accomplished that goal in 2021, I got pregnant with Austin—almost on our first try.

He was healthy, and when he was about 18 months old, we felt ready to try again. We wanted our children close together—to stay in the thick of those really young years rather than leave them and have to go back.

Once again, I was lucky to get pregnant quickly. We found out in November 2023 and told our close family right away. I was super excited—I just can’t keep a secret.

Around Christmas, when I was about 12 weeks along, we posted a photo of Austin on Facebook, announcing that he was going to be a big brother.

I’m an oncology nurse and work at an inpatient oncology clinic at a major Wisconsin hospital. My OB-GYN worked at the same hospital, and I had worked in the operating room with her many times—I knew her well personally.

So when I was having my exam and the ultrasound technician left the room to get her, she came in quickly. She had her laptop open and said, “I want to show you some of these things.”

His blood was flowing backwards

My doctor played the image of Connor’s blood flow into his heart. She pointed out that his heart had four different defects, and because of that, his blood was actually flowing in a backward direction.

If he was born at full term, his body would not circulate oxygen-rich blood—it would pool in the middle of his heart. It’s a condition called Tetralogy of Fallot.

I’d heard of this condition in nursing school, and I knew it was serious. But if that had been the only thing wrong, we could have followed up with a specialist after our baby was born to see if it was fixable with surgery.

However, my OB-GYN continued. She showed us his kidneys, which were enlarged and covered with cysts. She explained that they weren’t functioning, and that he had never developed a bladder.

In the womb, the baby breathes in the mom’s amniotic fluid and then pees it back out. This creates more amniotic fluid and helps develop the baby’s lungs.

Because Connor didn’t have kidneys or a bladder, he wouldn’t be able to pee and increase the amniotic fluid. Without enough amniotic fluid, his lungs couldn’t develop enough to breathe air.

After my OB-GYN explained everything, she turned to us and said, “I’m really sorry, but this, for me, would be a diagnosis of ‘incompatibility with life.’ You’ll need to follow up with a maternal fetal medicine doctor to make sure they see what I’m seeing.”

But I could read it in her face—she was certain.

I was shell-shocked.

My OB-GYN stood up and asked, “Can I hug you? What can I do for you?”

I told her I didn’t know what I needed. I tried not to break down because I didn’t think I’d make it out of her office if I did.

The thought racing through my mind was: “My poor baby. He’s never going to live outside of my body, like this little boy I’d been envisioning playing with Austin and being best buds. It’s all just going to be a dream that I had.”

It was wild, because I could feel him moving inside me; he was alive and safe. But he would never be able to do that outside my body. It was spinning in my mind that pretty soon he wouldn’t be with me anymore.

Brian was quiet through all of this, just holding my hand to comfort me.

My OB-GYN made an appointment for a maternal fetal medicine doctor to see us two days later.

I was like a zombie in my house for those two days, wavering between falling apart because he was kicking and, when he wasn’t, worrying, “Oh gosh, is he even alive anymore?”

I went through a lot of anxiety, grief, and crying. Brian realized it was much harder for me since he couldn’t feel the baby inside.

Brian’s mom took Austin to her house, and I told my manager I wouldn’t be at work for a few days. She reassured me, “We’re here for you—take as much time as you need.” I can’t thank her enough for all the support.

At the second anatomy scan, the ultrasounds took two hours and the maternal fetal medicine specialist confirmed all the same problems my OB-GYN had seen.

He told us that the fetal anomalies could be caused by a genetic issue so rare it wouldn’t have been caught in prescreening, and it wouldn’t likely happen again.

He recommended terminating the pregnancy because I was so low on amniotic fluid that Connor would most likely pass away before birth, which would put me at serious risk for infection.

Brian and I were prepared for the news. I went into planning mode automatically to keep myself from feeling in the moment.

We found that although abortion was still legal in Wisconsin up to 22 weeks, and I qualified for a D&E (dilation and evacuation), my doctor and his staff knew of only two hospitals in the state that would perform a termination at my stage.

Plus, in Wisconsin I would need to undergo a legally required third ultrasound, counseling, and, after all that, a 24-hour wait before the procedure.

I was aware Wisconsin had an abortion ban, but I was shocked to learn only two hospitals would do D&Es for someone 20 weeks pregnant.

There was so much nonsense just for a woman to get essential care.

If a patient needs chemo, they get to decide whether to do it or not

A third ultrasound sounded painfully traumatic—I didn’t want to watch my baby on screen again, and I didn’t need counseling for options that didn’t apply to him.

Then to have to wait another 24 hours to get the termination done so I could start to grieve—it sounded awful. You want finality.

The law really pissed me off. Why did some old guy in politics care about my health care? He wasn’t in that ultrasound room or carrying a baby that couldn’t live. Why does it matter to him?

Sometimes, I think about abortion at work. If a patient needs chemotherapy, they get to decide whether or not to do it.

Nobody comes in and says, “You know what? I don’t agree with chemotherapy, so you can’t have it.”

It’s baffling that the law can dictate a health care decision.

That’s why we asked the specialist if there was another option. He recommended Northwestern Medicine Center in Chicago.

Fortunately, I got an appointment just a couple of days later, and we drove the two and a half hours for the first part of a two-day procedure. Since I was so far along, the abortion couldn’t be done in a single day.

First, they gave me a pill to stop the baby’s heart. Then the doctor inserted thin seaweed sticks into my cervix to dilate it. It only took 10 minutes, but even with lidocaine for pain, it was more painful than giving birth.

I had to lie flat on my back in our van on the way home because I was cramping so badly I couldn’t sit upright. I was so glad that my mother-in-law could take Austin, because I couldn’t be a mom that night. I was in terrible pain for about six hours.

By the next morning, I felt fine for the drive back to Chicago. It was a quiet ride. Neither Brian nor I wanted to talk about what we were about to do.

During pre-surgery, a social worker talked to us about funeral homes that could cremate our baby. That’s not something you ever want to plan for your child—it was rough.

But I only started to cry when staff came to get me for the final part of the abortion. Brian leaned over and kissed my belly, and that’s when he cried. When he cried, I just lost it.

It was one of the hardest moments of my life.

I don’t remember the procedure, but when I was coming out of anesthesia I scared Brian because I kept yelling at the nurses, “Bring me my baby. Where was my baby?”

They had to give me medication to calm me so I could sleep. I remember knowing, logically, there wasn’t a baby. But my heart and body kept saying, “He’s not there, so he must be somewhere else.” It was just primal.

Days in slow motion

It took a while once I got home for that feeling to fade. I would wake up panicking at night, thinking I’d lost my baby or forgotten him in bed. I had to remind myself he wasn’t there.

After I was home, it was hard to get back into things. I struggled and felt like I was moving in slow motion. I took a week off work—I couldn’t walk through the hospital doors where I first got Connor’s diagnosis.

I wrote a lot of letters to Connor when I was emotional, upset, or angry, or just thinking about him a lot. That helped.

I received a huge amount of support from many people, even those I didn’t expect. That opened a door for me to use this experience to help other moms.

Nobody should have to go through this kind of trauma and then worry about getting care or have people tell them they can’t.

I joined an online support group, and it was eye-opening. I thought, “Wow, there are all these moms feeling the same way I am. This mom had the exact same diagnosis.” Having ears to listen when nobody else in my life had experienced what I had helped me so much.

When Brian and I decided to try for another baby after losing Connor, it was a hard decision. Sometimes I felt I was in a good place, but other days I was so depressed I couldn’t imagine having another child.

After a couple of months, we tried, and I got pregnant right away. Unfortunately, I had a very early miscarriage, which set me back emotionally. I questioned whether I could ever have more children.

But when I felt better, we tried again and I got pregnant once more.

I was very anxious that we’d lose that one too, but she stayed, and was born a month early.

I’m so glad she’s a girl, that she came after such trying times, and was in my belly when I spoke before Congress. I think it will set her up for a vibrant, outspoken life.

Her name is Madelynn Lee, and she’s 10 months old.

I’m excited to tell Maddie she can be whatever she wants to be—and that her mom will keep fighting for her to have the best life possible by telling my story.

When their girlfriends needed abortion care, they showed up

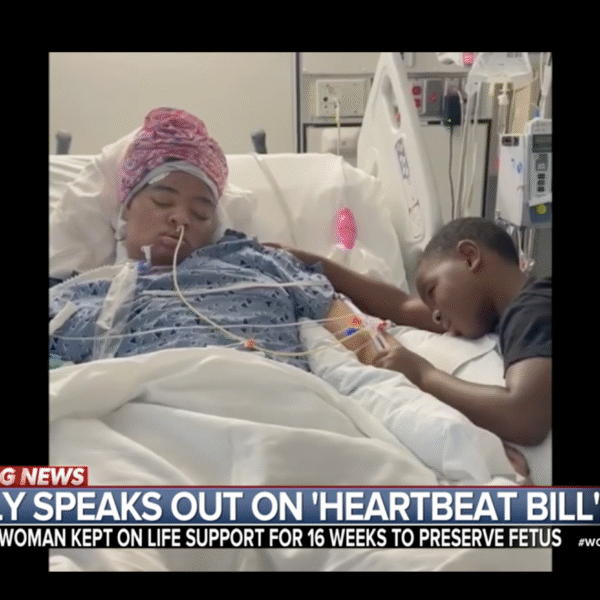

Mother whose daughter was kept on life support due to abortion ban speaks out