For one Louisiana mom, speaking out about reproductive health care is a way of honoring her son’s memory

In the context of Louisiana’s current legal and political environment, the story of Ginny Engholm’s 2009 abortion is unique: She got the care she needed, and felt comforted and supported by her doctors.

For Ginny, sharing her experience years later still brings up a range of emotions. At the time, she and her husband, Scott, were thrilled to be expecting a baby. But at their 20-week ultrasound appointment, they learned that their son had a condition called Trisomy 18. “It’s what’s called a catastrophic fetal diagnosis,” Ginny recounted to StoryCorps producer Mia Warren. “Which basically means that it’s considered incompatible with life.”

But in Louisiana in 2009, long before Roe v. Wade was overturned, Ginny recalled, “if … you decided that you wanted to end the pregnancy, they would admit you to the hospital like they do any other mother. They would induce you.”

“After everything happened, you feel you have to defend yourself, because people think such horrible things about people who make this choice,” Ginny said. “And post-Roe, I was surprised at how much pain I felt and honestly, how much I would think about [my son] Harrison and feel those emotions again. And the thing that really made it so hard is just knowing that there are women all over the state and the country who are going through the terrible experience that I had. And they’re going through it in circumstances even worse.”

Ginny remembered her son Harrison in a conversation recorded by StoryCorps Studios as part of Abortion in America’s collection of interviews with people in Louisiana about the ways in which the state’s abortion ban has affected their lives. This project was produced in collaboration with Glamour and the Newcomb Institute at Tulane University.

I think that people put late-term abortion in a very specific box and they don’t know that many, many women that they know probably had one.

Audio Transcript

Ginny Engholm: I’m just talking my husband’s ear off and being all chatty and the tech is getting more and more quiet. And then she doesn’t tell us if we’re having a boy or a girl. She just says that we need to meet with the doctor, and they take us into the doctor’s office. He took my hand, he looked in my eyes, and he said, “I have some terrible news about your baby.”

Our son had something called Trisomy 18. It’s a problem with the way that your chromosomes develop and it’s what’s called a catastrophic fetal diagnosis, which basically means that it’s considered incompatible with life.

My husband and I had been offered testing earlier in the pregnancy and we had declined it, because we said nothing would make us end this pregnancy. I had no idea that there were things that were worse than the worst that we could imagine.

I think people put late-term abortion in a very specific box and they don’t know that many, many women that they know have probably had one. And for almost every single one of those women, some terrible tragedy has happened that’s created that scenario for them. It’s a process that no one would go through unless they had to.

And in 2009, if you lived in a state like this and you were facing a catastrophic fetal diagnosis, and you had decided that you wanted to end the pregnancy, they would admit you to the hospital like they do any other mother. They would induce you.

So, we went to the hospital and they took me up to the room and hooked me up to the IV, and they gave me an epidural. I remember they had, like, little stickers that they put on the door that were, like, tears, so that all the nurses and doctors who came in and out would know we weren’t having a healthy, happy baby. Everyone treated me and my husband with such dignity and compassion. No one remotely made me feel judged or like I was doing anything wrong.

My son Harrison was stillborn, but they let me hold him as long as I wanted. I held him for nine hours. You know, the entirety of all of my relationship with him, and my husband’s relationship with him, is wrapped up in those nine hours. We got to bathe him and dress him, and take pictures with him.

After everything happened, you feel like you have to defend yourself, because people think such horrible things about people who make this choice. And post-Roe, I was surprised at how much pain I felt and honestly, how much I would think about Harrison and feel those emotions again. And the thing that really made it so hard is just knowing that there are women all over the state and the country who are going through the terrible experience that I had. And they’re going through it in circumstances even worse.

Harrison’s death wasn’t a matter of if he died, but when he died. And I can take some comfort in knowing that he only ever existed in the warmth of my body. He heard my heart beating and felt lulled by that. I knew that I had given my son the only thing I could give him, which was a life without pain. And I only did it because of love for him.

When their girlfriends needed abortion care, they showed up

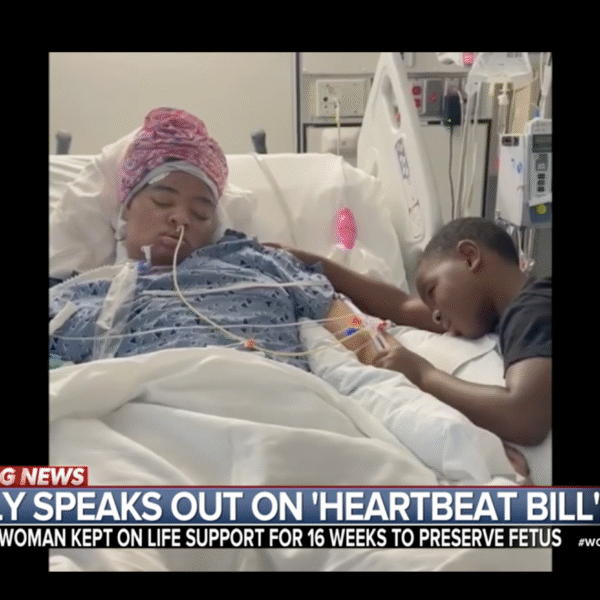

Mother whose daughter was kept on life support due to abortion ban speaks out