“What Can I Even Say Without Having to Go to Jail?”

This story was originally published by Mother Jones

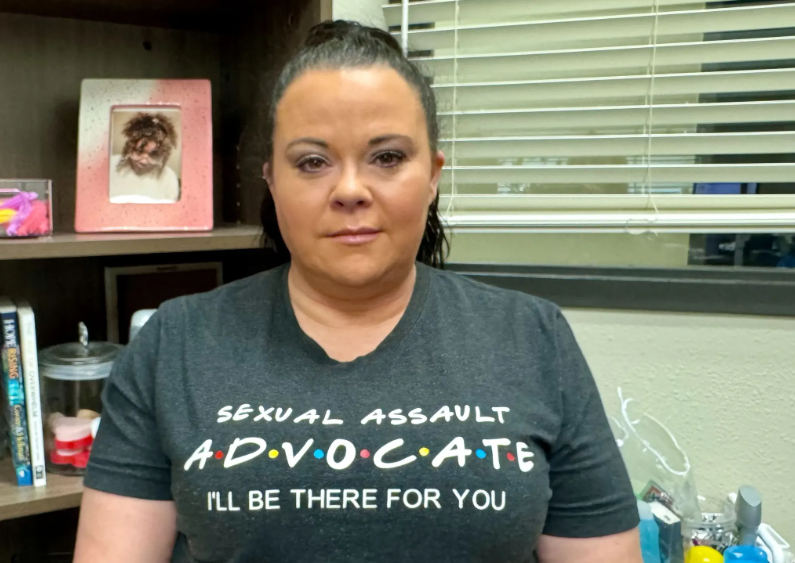

When Heather Williams, an advocate with the Tulsa-based nonprofit Domestic Violence Intervention Services, gets a call from the local hospital, she has to drop whatever she’s doing and go.

The call normally comes in when a survivor of sexual assault has arrived at the hospital and is preparing to undergo a sexual assault forensic exam, used to collect DNA evidence. Williams’ role is to be at the survivor’s bedside, providing emotional support—by offering words of comfort or holding their hand—and giving the survivor information about the resources they could turn to for further help, like reporting to the police or seeking therapy.

But one day last year, she encountered a new challenge: For the first time in her three and a half years on the job, Williams watched as her client got the news that she had become pregnant after being raped by her ex-partner.

“She just sat there, frozen, and then just starts crying,” Williams recalled. Everyone in the room tried to comfort her, hugging her and telling her, “It’s okay, you’re gonna get through this.”

But privately, Williams wasn’t so sure.

If her client had gotten the pregnancy result about a year before, Williams would have told her she had options: Abortion used to be legal in Oklahoma up to 20 weeks’ gestation (though it was difficult to access; there were few clinics, and patients were required to wait 72 hours and have an ultrasound before having the procedure, among other barriers). Nearby states like Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico—where abortion is still mostly legal—also have clinics Williams’ client could have traveled to in a pinch. But in May 2022, Oklahoma’s Republican governor, Kevin Stitt, passed two citizen-enforced, near-total anti-abortion bills—both of which the Oklahoma Supreme Court later found unconstitutional. After the Supreme Court handed down the decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in June 2022, overturning the constitutional right to abortion first established in Roe v. Wade, Oklahoma enacted a law banning abortion, with an exception only to save the life of the mother. The law threatens abortion providers with two to five years in prison on a felony charge. So by last summer, when Williams’ client found out she was pregnant by her rapist, there was nowhere left in Oklahoma for her to get a legal abortion.

If Williams didn’t have to worry about the consequences, she might have told the woman where else she could still get a legal abortion, or referred her to a local reproductive rights organization that could provide more information. But she hadn’t even researched where abortion is still legal, because she was afraid of saying something that would put her at risk, given that her state has also made “aiding and abetting” an abortion illegal—though it’s unclear what, specifically, that means. (A spokesperson for Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond didn’t respond to my questions about whether advocates could be prosecuted for mentioning abortion as an option to survivors or giving them information on where it is still legal.)

“Her only recourse,” Williams recalled thinking, “is either she’s gonna keep it or adopt it out.”

In 2018, staff at Williams’ agency took their first course with Provide, a national nonprofit that gives free trainings to domestic and sexual violence treatment and prevention organizations on how to offer what’s known as all-options counseling to pregnant people. This includes information on carrying to term and parenting, putting their baby up for adoption, or having an abortion. The lessons emphasized that “we are not to insert our own values, judgments, or opinions on what someone believes is best for themselves,” Margaret Black, the agency’s vice president of clinical services, told me.

But that’s easier said then done when state lawmakers are forcing their morals on everyone else. It’s ultimately up to individual advocates like Williams to decide how much information to give to a pregnant survivor—and, in the process, how much legal risk they’re willing to shoulder if they do discuss abortion. Since Dobbs, 16 states have banned abortion almost entirely or at six weeks’ gestation, which is before most people know they’re pregnant. Nine states have laws that prohibit helping someone get an abortion, whether by mailing them pills, assisting a minor in accessing abortion, or otherwise “aiding and abetting.” New data shows the scope of the problem faced by advocates like Williams, who are often underpaid and already tasked with emotionally grueling work. A study published in February in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons found that, under Roe, pregnant and postpartum people in states with abortion restrictions had a 75 percent higher rate of homicide than those in states that protected abortion access. Another study, published in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine in January, estimated that there were more than 64,500 pregnancies as a result of rape in 14 states with abortion bans after the Dobbs decision, with the majority—nearly 59,000—occurring in nine states with abortion bans that lack exceptions for rape or incest.

Across the country, domestic and sexual violence treatment and prevention programs are run by state-led, federally funded coalitions tasked with overseeing organizations in their state. These groups, in theory, should be grappling with how to incorporate information about state abortion bans into advocates’ daily work. To better understand how that was playing out, I contacted the 24 coalitions in the 16 states with near-total bans (some states have separate coalitions for domestic and sexual violence agencies, while others are combined). Just 13 of those coalitions told me they’d discussed the details of their state’s ban with the advocates providing services to survivors. Most others declined to comment or didn’t respond to my inquiries, except for a representative for the Mississippi coalition—their state prohibits abortions with exceptions for the life of the pregnant person or in cases of rape and incest reported to police—who was the only one who admitted their coalition doesn’t address the issue with advocates at all. And Kentucky—where abortion is banned except to save the pregnant person’s life or prevent serious health risks—was the only coalition of the 13 that said they’ve discussed the ban whose spokesperson admitted to me that the agency advises their member organizations not to discuss abortion with survivors.

Ondine Quinn, the director of program development at Provide, the organization that provides trainings on offering counseling, told me she sees not addressing the bans head-on as a dereliction of duty: “They have to put out guidance to their staff, they just have to—they can’t just ignore the issue and allow people to then individually make decisions about whether they can or cannot say something.”

So far, no advocates have been prosecuted for giving survivors information on how to access abortion—which Sara Ainsworth, senior legal and policy director at the national reproductive justice legal advocacy nonprofit If/When/How, attributes to the fact that “it’s not illegal to share information about abortion in any state under the First Amendment protected rights [to free speech].” But in states like Oklahoma and Texas, where it’s a crime to “aid and abet” someone seeking an abortion, some advocates worry that neither the First Amendment nor the confidentiality statutes that protect communication between advocates and survivors in many states would prevent them from potentially facing prosecution if they share information with a survivor on accessing abortion.

“We don’t know,” said Alicia Aiken, director of the Confidentiality Institute at the Danu Center, a strategic advocacy organization where she trains service providers and advocates on protecting the privacy of survivors of violence. Whether advocates face prosecution for discussing abortion with survivors “is likely to play out very differently depending on the local conditions,” including the strength of a state’s confidentiality protections—which vary widely—and whether local prosecutors are motivated to pursue such cases against advocates, Aiken added.

Experts say the lack of clarity around what advocates can tell pregnant clients about abortion without putting themselves at legal risk can cause what academics and doctors have described as “moral injury,” the emotional turmoil that results from feeling forced to act contrary to one’s internal or professional code of ethics.

I ain’t trying to lose my whole livelihood because I’ve given someone this advice.

Advocates aren’t the only ones caught in the middle: Administrators at both the agencies that employ them and the state-level coalitions that are supposed to act as leaders and resource hubs are often unsure of what’s legal and what’s not, and worry that issuing clear guidance to their service providers could put their funding at risk. “We’re hearing a lot of anger from people who have gone into this work because they care deeply about supporting survivors and their lives and making sure people have dignity and access to care,” said Quinn, from Provide. “They feel that their hands are tied.”

Williams, the advocate in Tulsa, is a 47-year-old former cop who wore her hair pulled back tight and her face makeup-free when we met a few weeks before Christmas; on her days off, she said, she indulges in Botox and salon visits to decompress from the intensity of work. She likens herself to a “bulldog”: “I will fight for my victims like there’s no tomorrow,” she told me. But when she’s working with survivors with unwanted pregnancies, she’s become more cautious. “I think it’s just so new to us that we’re all so afraid to even touch it,” she said of discussing abortion in light of the state’s ban. Agency administrators said that Williams speaks only for herself and not for the organization as a whole, and that advocates can always seek guidance from, or refer their client to, another team member.

But for Williams, the uncertainty can feel overwhelming: “I ain’t trying to lose my whole livelihood because I’ve given someone this advice.”

Laurel Williamson

The roles of domestic and sexual violence advocates can take many forms. They may answer calls on a hotline; accompany a survivor at a hospital as they undergo a sexual assault forensic exam; help them file a police report or access a shelter; go with them to court; and work with them to create a “safety plan” to minimize their risk of future danger from an abusive partner.

This work is both emotionally and logistically difficult, as a report published last spring by the National Network to End Domestic Violence outlines: The average starting salary for a full-time domestic violence advocate is just over $40,100. The low pay, combined with “the ongoing impacts of factors like burnout, vicarious trauma, irregular hours, and continued exposure to COVID-19,” has made it especially hard to retain advocates in recent years, the report notes. And the Dobbs decision hasn’t helped: Advocates “must now also navigate an uncertain legal landscape that may criminalize them and the work they do to ensure survivors have control over their own decisions and lives.”

Since October 2021, federally funded reproductive health care organizations such as Planned Parenthood have been required by law to provide all-options counseling, though they’re not permitted to encourage abortion. There isn’t an equivalent legal requirement for domestic and sexual violence–focused organizations that receive federal funding, according to spokespeople for the Department of Justice and Department of Health and Human Services, which fund them. Still, many of these agencies offer advice on parenting, adoption, and obtaining abortions, because most advocates believe that survivors deserve to have accurate information about all of their options. “I think people sometimes don’t understand the brutality of what sexual and domestic violence is, and how it removes autonomy,” said Sara Barber, executive director of the South Carolina Coalition Against Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault. “So if you’re responding to somebody, it’s a really important part that you restore that sense of autonomy.”

“If somebody decides they want to keep a child, that, too, is a valid decision,” Barber added.

But for people trapped in abusive relationships, that decision isn’t without risk. Domestic violence often starts or intensifies during pregnancy, when abusers may begin or increase their abuse if they don’t have the tools to cope with stress about finances, an unplanned pregnancy, or jealousy about the attention a pregnancy will take from them, according to March of Dimes, a maternal and infant health advocacy group. Homicide is a leading cause of death for pregnant people in the United States, CDC data shows—a fact that researchers attribute to the prevalence of both firearms and intimate partner violence; a 2020 study published in the American Journal of Public Health found that more than half of the 189 pregnancy-associated homicides—characterized as occurring during pregnancy or in the first year postpartum—that occurred that year happened at home.

A 2015 review of studies on the relationship between intimate partner violence and maternal and neonatal health, published in the Journal of Women’s Health, notes that pregnant people who are abused by a partner are less likely to receive timely prenatal care and more likely to report symptoms of depression both during pregnancy and after giving birth. It’s also risky for the fetus, increasing the likelihood of low birth weight, preterm birth, and even fetal death. After a baby is born, sharing a child can also make it harder for a victim to cut ties with an abusive partner: A 2014 study published in the journal BMC Medicine found that women who were unable to get wanted abortions were more likely to experience “sustained physical violence” and “sustained contact” with an abuser over time, while those who were able to obtain abortions experienced less physical violence and ended their relationships with their abusive partners sooner than those who gave birth.

Some abusers use repeated, forced pregnancies as a tactic to keep victims under their control, experts say. “We’ve had a few patients come in saying that [their abusers] just keep the patient pregnant so they can’t leave,” Kasey Magness, forensic nurse administrator at the Tulsa Police Department, told me. Crystal Justice, the chief external affairs officer for the National Domestic Violence Hotline, recounted the story of an 18-year-old caller who’d told a hotline advocate she became pregnant after her abusive partner refused to let her use contraception and threatened to kill her; another, also an 18-year-old woman, reported getting pregnant after her abusive partner sexually assaulted her in a state with an abortion ban.

We’ve had a few patients come in saying that [their abusers] just keep the patient pregnant so they can’t leave.

Refusing a victim access to birth control is another common tactic of abusers, experts say. These practices—as well as preventing someone from getting an abortion, or, less commonly, a partner forcing them to have one against their will—are all forms of reproductive coercion, which the National Domestic Violence Hotline defines as “threats or acts of violence against a partner’s reproductive health or reproductive decision-making.” While reproductive coercion itself isn’t explicitly outlawed, “some conduct that would be considered reproductive coercion is already a crime,” such as sexual assault, according to Ainsworth, the senior legal and policy director at If/When/How.

The little data that exists shows that reproductive coercion is increasing alongside rising abortion restrictions. The National Domestic Violence Hotline says 2,441 callers reported experiencing some form of reproductive coercion in the year after Dobbs, compared with 1,230 callers who made those reports in the year before the Supreme Court decision. That’s a 98 percent increase—and it’s likely an undercount, given that domestic and sexual violence remains underreported overall, according to Justice.

The impact disproportionately affects marginalized communities. While about 41 percent of women and just over a quarter of men have experienced sexual or physical violence or stalking from an intimate partner, people of color in particular experience especially high rates, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Nearly 64 percent of multiracial women and more than half of Native and Black women (about 58 and 54 percent, respectively) reported experiencing those forms of abuse in their lifetime, compared with 48 percent of White women and 27 percent of Asian or Pacific Islander women. Research shows that LGBTQ people also face elevated rates of intimate partner violence and sexual abuse compared with cisgender and heterosexual people, with bisexual women and transgender people experiencing especially high rates, according to a 2015 report from the Williams Institute, a think tank based at UCLA Law.

Liz Tobin-Tyler, an associate professor of health services, policy, and practice at Brown University who has written about the interactions between abortion restrictions and intimate partner violence, told me she isn’t surprised that reproductive coercion is increasing as abortion restrictions rise. “When the state is saying, ‘You do not have choices [about reproductive health care],’” she said, “in a way, that signals to an abusive partner, ‘The state’s not giving you this choice, I already have this under control, so I therefore do not need to give you this choice either.’”

Some of those who oppose abortion see it differently. Darrell Weaver, a Republican state senator in Oklahoma—where Williams works—has been a staunch advocate for victims of domestic violence. Last year, he successfully pushed a bill making the first offense of domestic violence against a pregnant woman a felony rather than a misdemeanor, and increased the punishment for perpetrators from one year to five years in prison.

But Weaver is opposed to abortion, and has consistently voted in favor of abortion restrictions. He declined to tell me whether he’d vote in support of rape or incest exceptions, and said he doesn’t see a connection between abortion access and the domestic violence issues he’s taken up.

He does, though, have something in common with some of the domestic violence advocates I spoke with who support abortion rights: Weaver worries that discussing a “hot topic” like abortion in conjunction with domestic violence could curtail support for efforts to tackle the latter.

“If we clutter up these concepts,” he said, “then it’s going to diminish what we want to do.”

Lila Rose, founder and president of Live Action, a national nonprofit anti-abortion organization, said in an email that while “domestic abuse is a horrific and tragic crime that must be taken seriously…killing a child through abortion is not the answer.” She noted that Live Action does not support rape or incest exceptions to abortion bans.

As an attorney and director of law and policy for the Idaho Coalition Against Sexual & Domestic Violence, Lourdes Matsumoto has gotten a lot of questions from advocates in her state about navigating the total abortion ban that took effect in August 2022. Many of their concerns, she said, highlight the same fundamental fear: “What can I even say without having to go to jail?”

“People want to know, ‘How can I give out information but keep myself safe from prosecution?’” added Matsumoto.

Idaho has some of the most stringent abortion restrictions on the books. Performing the procedure is punishable by up to five years in prison, except when “necessary to prevent the death of a pregnant woman” or in cases of rape and incest reported to law enforcement or child protective services. Matsumoto is a plaintiff in a lawsuit against Idaho Attorney General Raúl Labrador, alleging that the state’s so-called abortion trafficking law—which says an adult who helps a minor obtain an abortion without parental consent can be charged with a felony—violates constitutional rights to interstate travel and freedom of speech and association. A federal judge temporarily barred that law from taking effect in November while Matsumoto’s lawsuit works its way through the courts.

People want to know, ‘How can I give out information but keep myself safe from prosecution?’

But for advocates, the rapidly shifting legal landscape can make it harder to know what they’re allowed to tell survivors about accessing abortion at any given time, and more difficult for legal experts to give organizations advice, Matsumoto said. “It makes it very difficult to safely be like, ‘Go ahead and say this today,’ because tomorrow, I might call you and say, ‘No, don’t say that,’ and you might miss my call, and then you might actually break the law,” she said, adding that the coalition has held several meetings to discuss what advocates can safely tell pregnant survivors about their options, as well as what kind of conversations would be riskier and could benefit from a lawyer’s input.

Idaho is one of the states with a law that protects communications between advocates and their clients. Such laws vary widely nationwide but most seek to reduce the likelihood that an advocate could be legally forced to divulge what a survivor has shared with them. How this would ultimately play out in states where abortion is now illegal remains unclear, said Aiken, from the Confidentiality Institute. She pointed out that other forms of privileged communications—between lawyers and their clients, for example—historically haven’t protected professionals who have committed a crime within the context of those relationships. Initially, after Idaho’s law passed in 2022, Matsumoto said she and others at the coalition “were hopeful” that it could provide “some protections” to advocates post-Dobbs. But with the passage of the abortion trafficking law last year—combined with the 2021 passage of a law prohibiting employees of agencies that receive public funding from promoting or referring people to abortion—the confidentiality clause could be practically meaningless: Those other laws may supersede it if an advocate was suspected of having helped a client obtain an abortion, Matsumoto said. (The Idaho AG’s office declined to respond to my questions.)

Bills that propose prohibiting public dollars from flowing to agencies that provide abortion information or referrals also appear to be on the rise. Last year, three states—Arkansas, Florida, and Tennessee—enacted legislation that bars public funds from supporting abortion access, and similar bills were introduced in 18 states, according to the Guttmacher Institute, an abortion policy research and advocacy organization. For domestic and sexual violence organizations—which typically subsist on a combination of state and federal funding and private donations—such legislation can effectively stop staffers from discussing abortion options with pregnant clients, or at least make them fear doing so.

In Kentucky, a law passed in 2022 makes it illegal for agencies to use any public funding to “directly or indirectly” refer people to abortions or counsel in favor of them. According to a spokesperson for ZeroV, the statewide coalition focused on intimate partner violence prevention, that law effectively bans their programs from presenting abortion as an option to survivors, since about 30 percent of their funding comes from the state. “Our programs abide by that law and do not make referrals for abortion so that they can continue to get state funding, which they need to keep their doors open,” Angela Conway, senior communication programs specialist ZeroV, said in a statement before declining to respond to follow-up questions.

Someone who works in domestic and sexual violence prevention in Missouri, and also declined to be named for fear of retaliation, said that a similar bill limiting public funding, proposed last year, “raised a really big concern for our advocates, because it’s a limit on conversations they could have with survivors [about abortion]—even if survivors were bringing it up and requesting the information.” That bill didn’t become law—but “even when things like that are proposed,” the source added, “it can cause a freezing effect with advocacy agencies.”

Some coalitions, however, are openly fighting back. A few months after the Supreme Court voted to overturn Roe v. Wade, Barber, the executive director of the South Carolina coalition, argued in an op-ed for the Post and Courier how “removing access to abortion care is devastating to victims of sexual and domestic violence.” The coalition also issued a statement outlining the stakes of abortion restrictions for survivors. And she and the coalition’s staff talked with their 22 member organizations throughout the state about the specifics of South Carolina’s restrictions on abortion, which include a six-week ban, and urged them to make internal policies about what information they’d provide to survivors about abortion. She sees this proactive approach as her duty: “My job is to speak to the needs of survivors,” she told me.

Ann Warner; Lissa Lucas

Tonia Thomas, a team coordinator of the West Virginia Coalition Against Domestic Violence, feels similarly. West Virginia—which has a total ban on abortion, with exceptions only for nonviable pregnancies, medical emergencies, and rape and incest if a survivor reports to law enforcement—is “probably the reddest state in the nation, and we still had the conversations” about how advocates should navigate abortion restrictions, Thomas said. Last January, the coalition partnered with WV Free, a local reproductive justice organization, to co-host a webinar on “counseling in the new landscape of abortion legality.” Nearly two dozen advocates from across the state attended. Representatives of coalitions in Indiana, Tennessee, Texas, and Georgia told me their agencies had made similar training efforts.

Not all the state coalitions have taken these measures, though. A representative for the Mississippi Coalition Against Domestic Violence acknowledged that the coalition doesn’t have discussions about the impacts of abortion restrictions on survivors. “That’s not something we talk about,” Tara Steverson, the Mississippi coalition’s communications and membership specialist, said.

But Stephanie Piper, the sexual assault program manager and victim advocate at the Gulf Coast Center for Nonviolence in Biloxi, Mississippi, does talk about it. Piper has continued to provide all-options counseling to pregnant survivors, including information on accessing abortion if that’s what someone wants. Having worked as an advocate for 13 years, Piper has seen enough survivors who resort to buying wire hangers or drinking bleach and ammonia to try to terminate a pregnancy to know that “if someone has been a victim of domestic violence or sexual assault and they do not want to continue to be pregnant by the person that had injured them, the risks are necessary,” she said. But still, she added, guidance from the Mississippi Coalition “would be a nice conversation starter, just to see where everybody is.”

Williams, the advocate in Tulsa, remembers getting an ultrasound during her own pregnancy more than 20 years ago, and hearing what would become her daughter’s heartbeat. That day came after five years of trying to get pregnant, she said, and that long, hard road to becoming a mom is part of what shaped her own views on abortion: “It’s not something I feel like I could ever do,” she told me, “but I’m not going to tell someone else what they can do or what’s right for them.”

Courtesy of Heather Williams

“I wish it was still available,” she added, “because there are some people that could use it.”

Williams doesn’t know what happened to the woman who found out she was pregnant by her rapist last year. Following up with clients can be difficult, Williams said; doing so can present dangers for the survivor, and some survivors don’t want to revisit discussing the trauma that led them to cross paths with her in the first place.

As a result, Williams said, “it’s so easy for people to fall through the cracks.”

Those are the people she wishes anti-abortion lawmakers had to answer to. “I wish they had to comfort them,” she said. “I wish they were the ones that had to tell them it’s going to be okay.”

This article was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2023 National Fellowship.

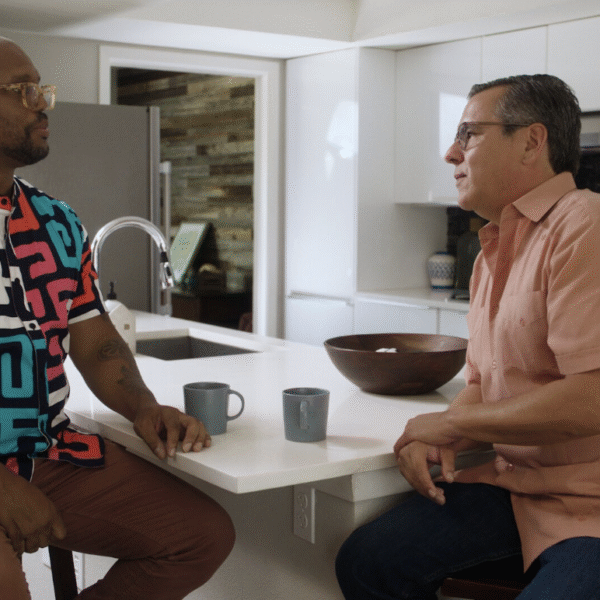

When their girlfriends needed abortion care, they showed up

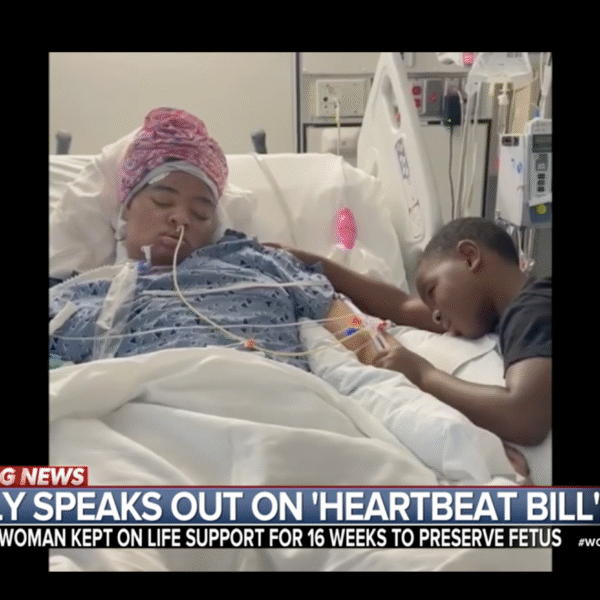

Mother whose daughter was kept on life support due to abortion ban speaks out