She Voted for Trump. Then She Had Two Terrifying Miscarriages in Texas.

Synopsis

In 2023, my sister Victoria spent more than 24 hours hemorrhaging into three diapers when Dallas-area hospitals declined to help her. “I know you’re not supposed to have regrets, but I do,” she said, about supporting Trump. “Look what’s happened.”

My sister Victoria was wrangling Elias, her then-2-year-old, into his costume on Halloween when the spots of blood in her underwear became worrisome. It was almost exactly two years ago, in 2022, and Elias had woken up from a nap excited about trick-or-treating. She’d gotten him into a shiny black firefighter hat, a yellow jacket with neon reflectors, kelly-green shoes, and a bright red hatchet — the color of the blood she could no longer ignore.

“I could feel it. That’s when I started to panic,” she told me last week. It was the first time we had spoken at length since 2018. “I was trying to hide it because it was Halloween, so the only thing I was thinking about was just making sure that I wasn’t spoiling the holiday for Elias.”

Our relationship was non-existent then, strained both by a traumatic childhood and the fractured ways we’d each coped. She was a busy toddler mom. I’d just been nominated for an Emmy. We were doing the best we could, but we butted heads. Meanwhile, people across the country were on edge, wondering what a midterm election would bring in the months after Roe v. Wade was overturned.

Now, with weeks to go before another Halloween — and another presidential election — she was explaining the terror-filled night she’d spent without me, when she faced the consequences of our state’s conservative agenda to outlaw abortion.

“I didn’t want Elias to notice anything was going on,” Victoria remembered. She put on Blippi songs in the car, trying to hide her fear as she drove down the North Central Expressway. She dropped Elias off at our mom’s before going to the hospital.

“It felt like the longest drive I’ve ever taken.”

***

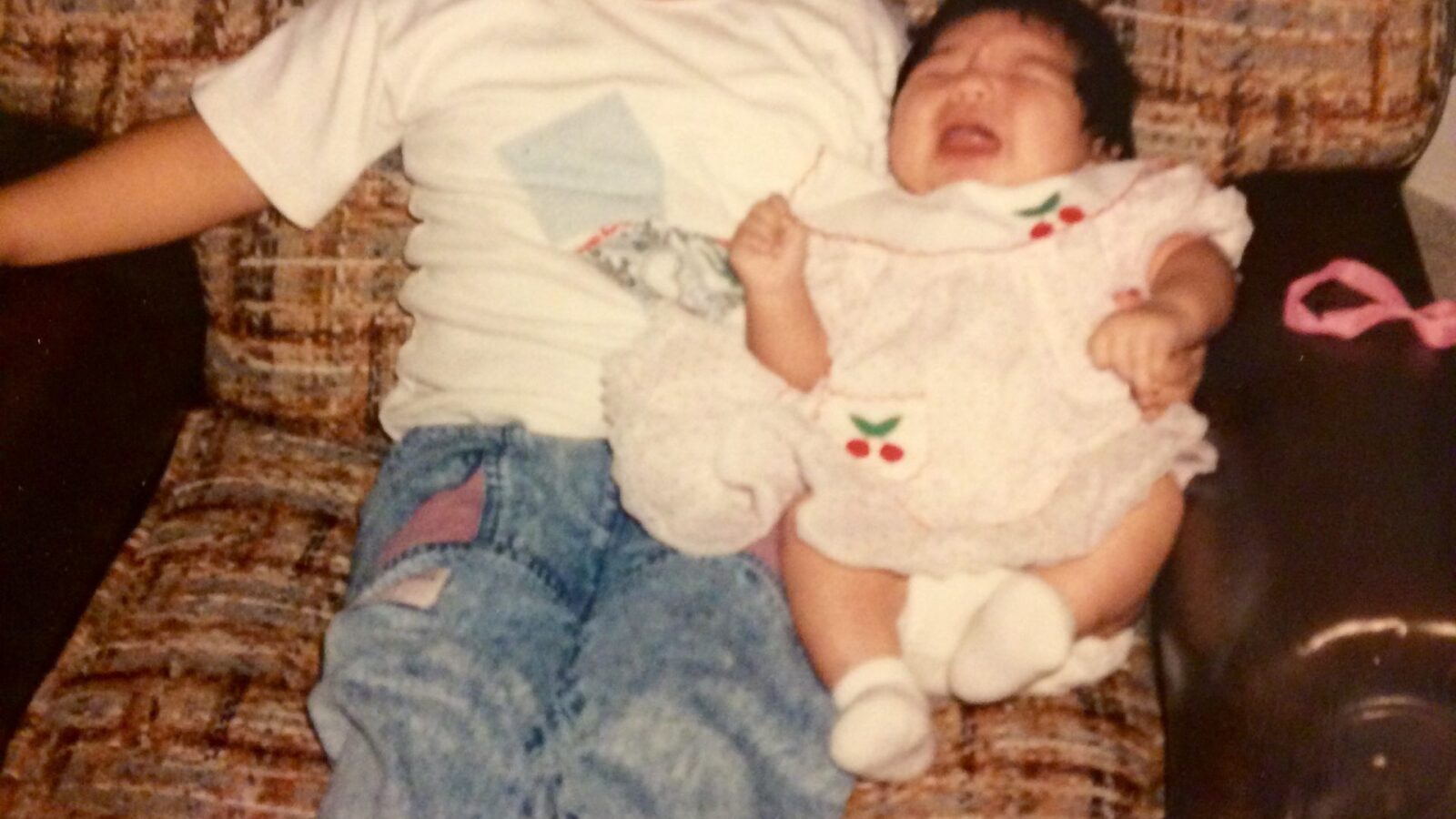

I still remember the day Victoria was born. I sat patiently on a woven metal bench with thick plastic coating in a cold waiting room at Dallas’ Parkland Hospital. My fingers were tiny enough to poke through the holes as I counted each one, waiting to meet my soon-to-be built-in best friend, my first hermanita. I had practiced holding her like I had done with all my baby dolls. I had big plans to help my mom pick out our matching outfits. At the direction of my dad, her namesake, I prepared to be her protector. I was proud to have such an important role, but it proved heavier than I imagined.

In retrospect, it must’ve been hard to be my younger sister. I was an over-achiever who coped with complex post-traumatic stress disorder by always doing the most and staying busy. I was a good student who sat at the front of the class. I followed the rules. I went to college, graduated, and got my dream job as a TV reporter. I won awards and stacked accolades. Growing up as the eldest daughter in an immigrant household, I was the man on the El Mundo lotería card holding up the world. I couldn’t mess up. Maybe not in so many words, but my parents constantly told my sister to be more like me.

Despite that, Victoria was different. She was the rebellious one, dancing and singing at the dinner table, always making up her own rules. She skipped school and snuck out. Despite desperate attempts by my very conservative (step)dad to tame her, she couldn’t be held down. I silently looked up to her in many ways. She was fearless of consequences, excellent at making friends, unapologetically sexy, and had a seductive personality that challenged authority. We couldn’t have been more different, from foods we liked (cheese pizza only for her; hawaiian and jalapeño for me), to music (she loved country; I loved hip hop and Reggaeton), to world views.

In 2016, I had a panic attack minutes before going on live TV at a campaign rally for then-presidential candidate Donald Trump. He and his supporters repeated more and more racist comments about immigrants and Mexicans. They decried “anchor babies” and said they’d build a wall so high that anyone who dared to climb it would fall to their death, landing in pieces. As the crowd cheered, I thought of my immigrant parents, and the sinking feeling that these verbal attacks were being normalized in mainstream politics only became heavier. Afterwards, I embarked on a healing journey, but it wasn’t perfect or simple.

Meanwhile, Victoria was ready to change things up. She quit her waitressing job, packed all her things, and moved to the mountains of Arkansas. She took a job selling cell phones and started hiking. Living life in a more rogue way. And right around the time I was feeling — in my bones — the danger of Trump’s racism, my sister found herself attracted to the brash New Yorker running for president. She could almost see herself in him — a little rough around the edges, rebellious, unapologetic.

“This guy is not a politician! He’s very blunt and upfront about what he’s speaking and what he’s believing in, like maybe that is what we need,” Victoria recalled thinking at the time.

That year, on Election Day, she voted for Trump.

***

Six years later — after Trump appointed three Supreme Court justices who each voted to overturn Roe v. Wade — my sister sat hemorrhaging for hours in the emergency waiting room in the conservative small town of Waxahachie.

“I remember just being in there and seeing these ambulances,” Victoria said. Our mother offered to stay at the ER with my sister. But Victoria wanted her to take her son trick-or-treating. “The only thing I cared about was just making sure Elias got his candy.”

She was nearly nine weeks pregnant. The life that was supposed to be growing inside her felt like it was flowing out in streams of blood. It was filling the thick pads she was wearing, and she feared any moment it would seep onto the glossy plastic blue chairs at Baylor Scott & White Medical Center.

“I’m bleeding uncontrollably, I can’t stop it, and no one can help me because everyone’s afraid of what will happen.” At least, that’s how it felt during those hours in the waiting room.

Just two months earlier, Texas’ trigger law had gone into effect, making abortion a felony punishable by life in prison. Experts warned the law would be a minefield. And it is.

In 2023, 20 women filed a lawsuit asking the state to clarify the state’s definition of its “medical emergency” exceptions. But this past May, the Center for Reproductive Rights reported that the Texas Supreme Court refused to clarify, denying the women’s claims. In other states, like in Georgia, women have died “preventable deaths” because doctors’ fears of prosecution have been pitted against the needs of their patients.

As the clock ticked, and Victoria bled, she and her partner Bryan desperately clung to each other’s hands, in shock. She was in desperate need of life-saving care — care that she started to believe she’d voted away her rights to. Time collapsed and expanded. After a few hours, she and her partner were finally called into a back room to check her vitals. Then they were escorted to an emergency room bed.

A doctor came into the room. She was a young woman. Cold. She asked them questions that felt like an interrogation. Then she performed an ultrasound before passing her off to a tech, who asked her to remove her boxer shorts for another, this time transvaginal, ultrasound.

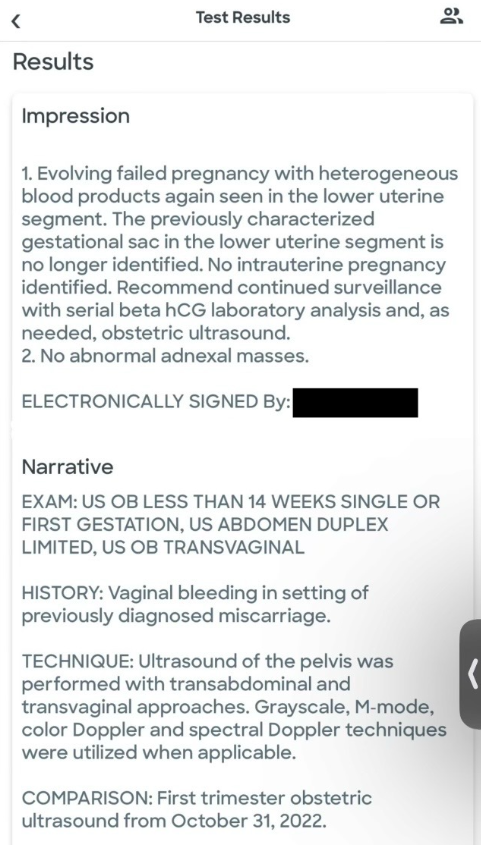

“I took them off, and the amount of blood that was on my legs, rushing down… I remember standing there, and I just started crying again,” Victoria said. Her email records from the hospital show both ultrasounds and describe her test results from the Oct. 31, 2022 visit as an “evolving failed pregnancy with heterogeneous blood products again seen in the lower uterine segment. The previously characterized gestational sac in the lower uterine segment is no longer identified. No intrauterine pregnancy identified.”

“It felt very morbid,” she said, tears rolling down her cheek. The delay in care, and then the tenor of the questions while sitting exposed in a cloth gown, made her feel numb. “It felt like it was the last stop, and this is where it all ends. There’s no turning around, and there’s no going to a recovery room afterwards.”

Nearly eight hours after they arrived, doctors finally determined that she needed medical care to save her life. She’s one of the lucky ones. Texas’ near-total abortion ban has a narrow exception for the life of the pregnant person. And what constitutes life-threatening remains murky. A study by health care consulting firm Manatt Health published this week found almost a third of OB-GYNs in Texas don’t have a clear understanding of the law, and 60% fear legal repercussions. Data released by the Gender Equity Policy Institute showed that since the abortion ban in 2021, the state’s rate of maternal mortality cases rose by 56%.

“After that, they cleaned (me) up, they brought me the pill, and they let me stay there for a while,” Victoria said. The pill, mifepristone, is used for abortion and miscarriage care. It helps by softening the cervix and breaking down the lining of the uterus. (Texas tried to ban that medication as well, but this past June, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the state’s challenges.)

“Eventually they brought in the discharge papers, and everything was done.”

The child would’ve been her second. They had settled on naming the baby Leonardo if it was a boy — Mila if it was a girl. The two held a small ceremony in Bryan’s backyard and buried her sonogram, along with a rattle his mother had made for them.

***

After her miscarriage that fall, Victoria and her partner spent winter in grief. But soon, spring brought the promise of new life. She was pregnant again.

“You can schedule blood work to find out the gender, and I had made that appointment, and I was very excited,” Victoria recalled.

This time, she said, her intuition made her sure it was a girl.

“I was throwing up a lot, I had a really sensitive stomach to everything, I was really sensitive to smells, and all the nurses were saying, ‘Oh, that typically means you’re having a girl!’” Victoria remembered. “There was something in me that said, ‘This one’s a girl.’”

She was cautious but excited. Once again, she and her partner had picked out a name for their child: This one would be Lilah Rose. They liked the way the name sounded, but that spring soon turned to summer.

She never made it to that appointment.

“I dropped (Elias) off at daycare. I was supposed to work that day, and I called in, and at this point I’m starting to bleed, and it’s a lot,” Victoria said. She kept this miscarriage a secret from our family. She’d always been the rebellious one, and with my parents already caring for her first son, she said she didn’t want to burden anyone.

It was August 2023. She called hospital after hospital, letting them know she was shy of 11 weeks pregnant and hemorrhaging. One Dallas-area hospital told her there was nothing they could do. Another told her they couldn’t help her. A third told her they needed to talk to her OB-GYN first.

No one would take the chance to help my sister. Like the dozens of women who sued the state that year after being denied healthcare due to the state’s anti-abortion laws.

“I was calling private hospitals,” Victoria said, fighting back tears. “I didn’t care how much it cost or how much money I didn’t have. I’m literally sitting in a vehicle riding around looking for someone to help me while there is life — that I was very excited about — coming out of me.”

She felt like she had let her partner down again. She said her bleeding got so bad that she drove herself to CVS and bought diapers. She went home and put them on and tried to wait it out overnight, but the scarlet blood kept coming. After more than 24 hours of hemorrhaging, and three drenched diapers, she finally made the decision to call Parkland Hospital the next morning, the place where I’d sat patiently 30 years ago on that woven bench. They said they would help her.

“We got in that little room, and all I remember is I didn’t want to look at anybody,” Victoria said. “I didn’t want to hear anything anymore. I just wanted them to help me, and I just wanted to leave.”

She remembered another long list of questions, another interrogation as if she were a criminal. As if she had done something wrong. But she hadn’t. She was just a mother having to grieve another wanted pregnancy, and the state was punishing her for it.

By now, she’d googled enough to know she needed a D&C.

A D&C, or dilation and curettage, is a procedure to remove tissue from inside a patient’s uterus. It is standard care for people experiencing pregnancy loss to remove tissue that can cause complications like sepsis. It’s also the same procedure used in some abortions.

Texas’ near-total ban on abortions has sown confusion in cases like Victoria’s, where medical professionals are hesitant to provide care that could be deemed abortive. Early research and news reports have shown that exceptions for the life of the pregnant person don’t account for the wide range of adverse health effects, including death, that can result from delays in receiving such care.

Two years after the ban was instituted, doctors are more confused than ever. Houston-based OB-GYN, Dr. Damala Karsan, said on Tuesday during a press conference that she and other colleagues fear arrests are inevitable for at least some doctors providing life-saving procedures to women experiencing miscarriages. “That’s probably how we’re going to figure out how sick you have to be,” said Dr. Karsan. Since the Texas Supreme Court refused to clarify “medical emergencies” for abortion exceptions, doctors will, as Dr. Karsan put it, continue “being pushed to walk that line.” That will eventually mean the death of mothers, as has happened in Georgia, or the arrest of the provider. She added: “Where is that line? Nobody knows. And so I think eventually some of us will probably have to go through the courts, through the jails, to figure that out.”

“Every woman who has come forward with a painful story of being denied care has lived in a state that claims to make allowances for women’s health,” Jessica Valenti wrote, in her new book, “Abortion: Our Bodies, Their Lies, and the Truths We Use to Win.”

“But when push comes to shove, they’re unable to get care,” said Valenti. “They’re not sick enough, or not close enough to death. Doctors around the country find themselves in the position of weighing their medical license and their freedom — against whether or not they should provide an abortion at that moment, or wait until their patient is just a little bit sicker.”

My sister’s story isn’t unique.

“I had a miscarriage post-Roe while visiting family in Texas in 2022,” one woman posted on X this week, in response to the U.S. Supreme Court decision on Monday to let Texas hospitals deny life-saving abortion care. “I almost died — after 7-8 hours of begging, I got an emergency D&C and transfusion. They don’t mind letting women die.”

Last August, for a second time, Victoria was lucky — doctors determined she met the exception.

A doctor finally came in and did the ultrasounds.

“When there’s a baby’s heartbeat you can hear it, but I mean, obviously I knew that wasn’t going to happen,” Victoria said. Again, tears welled up in her eyes. “I just wanted to close my eyes and I can just— there’s a part of me that kept thinking, like, ‘Well, maybe there is going to be a heartbeat,’ and this is just all, like, a fluke or something. But it’s like that little noise the ultrasound wand makes. And then finally, after that, they took me back into the room that I was in, and they started the procedure.”

She was in pain. She put her feet in the stirrups. They administered medicine for anesthesia.

“They let Bryan come in, and the only thing I told him was, ‘Just don’t tell my parents what’s going on.’ And he didn’t.”

***

On April 19, 2024, Victoria gave birth to Elias’s brother Leonardo. They’ve spent the summer in a mess of postpartum bliss and exhaustion. Certainly not thinking about Trump.

Then, three months after his birth, she was dealing with a colicky baby, working as a single mom, and trying to navigate work. One late night, in between feedings and getting Leonardo to sleep, she was scrolling on social media when she saw a video of presidential nominee Kamala Harris at the debate against Trump. She was talking about reproductive rights.

And suddenly it clicked.

“That is the sole reason that I’m voting for her,” Victoria said. “I’m 30 years old going through this.” To not be able to choose for herself, to have to run “around all over the city” for help, seemed ridiculous, and unimaginable for a teenager with less experience and resources. And clearly, considering Trump takes credit for the overturn of Roe v. Wade, this is his fault. She said, “This isn’t 1864.”

In 2016, Victoria said, “I don’t feel like I actually did any research.”

“I know you’re not supposed to have regrets, but I do,” she continued. “It was my fault because I also helped put Trump in the office, and now look what’s happened.”

Now, in a change that shocked even our mother, Victoria is asking family, friends, and coworkers if they’re registered to vote.

At a rally on Sept. 23, Trump told women: “You will be protected, and I will be your protector.” But that rings hollow to previous supporters like my sister now. And she might not be alone. In August, the Center for Reproductive Rights asked formerly anti-abortion folks what changed their minds. The more than 500 responses were harrowing and eerily familiar, and nearly all of them pointed to personal experiences: “Almost dying as I was bleeding and having a miscarriage at 16 weeks,” one woman wrote. “I was a married woman who had a very wanted pregnancy, and I still needed an abortion,” said another. “I’m a neonatal ICU nurse, and I’ve seen things that are worse than death,” wrote a third.

Earlier this week, when Vice President Harris appeared on the incredibly popular “Call Her Daddy” podcast, she criticized Trump for creating the exact problem my sister faced.

He “hand-selected three members of the United States Supreme Court with the intention that they would undo the protections of Roe v. Wade — and they did just as he intended, and there are now 20 states with Trump abortion bans, including bans that make no exceptions for rape or incest,” Harris said. “This is the same guy that said women should be punished for having abortions.”

“This guy is full of lies,” Harris continued. “I mean, I just have to be very candid with you.”

***

A few weeks after the debate, I reconnected with my sister. Call it fate. We were supposed to surprise my mom for her retirement dinner. I got stuck in traffic driving from Austin and was running late, so I asked Victoria if I could get ready at her place. She texted, “here, family is always welcome.” It felt really nice. That day, I got to hold her son and meet the 30-year-old Victoria, the mother of two. My sister.

She told me about the miscarriages. About Mila and Lilah Rose. About seeing the video of the vice president. And then she asked me about my life and my job. I’ve spent twelve years in the journalism industry, and she’d never really shown interest in what I do for a living. But here she was, sharing her story with me, and — now, after some thought — with you.

“A lot of the times,” she said, “women just accept what happens to them because that’s the way the world works. And that’s not how it should be like. Why can’t we fight for ourselves? Like, let me speak up.”

And ultimately, those traumatic experiences were so awful that they inspired her to do more research: “Why is Texas Republican all the time? Who are these people and what are they actually supporting? Are they actually doing us good, or are they doing us harm? They’re part of the problem, and how do I get them out?”

The Supreme Court’s decision this week means that, when it comes to reproductive healthcare, Texas does not have to abide by a long-standing law that requires most hospitals to provide stabilizing treatment to anyone who walks through their doors. If that sounds troubling, that’s because it is.

Any woman miscarrying in Texas can still be denied care because their doctor is afraid to be prosecuted. Still be forced to wear a diaper at home to absorb their blood in the middle of a physical and psychological trauma. Still get interrogated about their miscarriage.

On Wednesday, I heard Leonardo through the phone. He let out a whiney yelp and then a piercing cry. My sister’s time chatting was up, but not before she looked at him and kissed his forehead. “He’s the one that made it. He made it when the other ones didn’t,” Victoria said. “And maybe he’s here because I needed to learn to be the bigger person.”

Leonardo means lion-hearted or “brave as a lion.” He’s just a little guy, shy of 6 months, who brought my sister the bravery to decide for herself. And to help make sure others do the same.

“I feel like we’ve awoken a sleeping giant,” she said Wednesday.

“Who?” I asked.

“Women.”

When Politics Drives You From Home: 5 Americans Who Uprooted Their Lives Because of the State of the Nation

A pregnant mother in ICE detention says she’s bleeding — and hasn’t seen a doctor in weeks