A Mom Fled Texas for an Emergency Abortion. One Year Later She Had a Son and Gave Him Initials R.O.E.

Synopsis

This story has a happy ending. But “you have no idea the hell it took to get here,” Texan Taylor Edwards tells PEOPLE reporter Eileen Finan.

A lot of people have to have abortions to become mothers. I know it’s an uncomfortable reality, but it’s the truth.

Need to Know

- After years of trying for a baby, Taylor Edwards and her husband Travis were finally pregnant—but learned in her 17th week that the baby had a fatal birth defect.

- Texas law meant that unless she left the state, she had to try to carry her baby to term. They traveled to Colorado for an abortion in her 19th week.

- A year after their ordeal, the couple had a healthy son through IVF, and gave him the initials R.O.E. in honor of the landmark 1973 Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade.

When Taylor Edwards and her husband Travis first learned they were pregnant in late 2022, they were filled with joy—and relief. After more than two years of trying, and three rounds of IVF, they would be parents.

“With IVF and infertility, you are always waiting for the other shoe to drop,” says Edwards, 33. After she passed her 12-week mark into her second trimester, she felt like she could relax. “I was like, ‘Finally. I’ve run a marathon. I did it. It’s my turn to be a mom.'”

But when she and Travis, 34, went in for an ultrasound at 17 weeks in February of 2023, the imaging technician called in her doctor for a second look. “He gets to the back, and her skull and neck are not connected,” she recalls. “There’s a bubble-like structure. Her brain was coming out. And he says, ‘This baby’s not going to survive.’ I didn’t understand the words he was saying in that moment.”

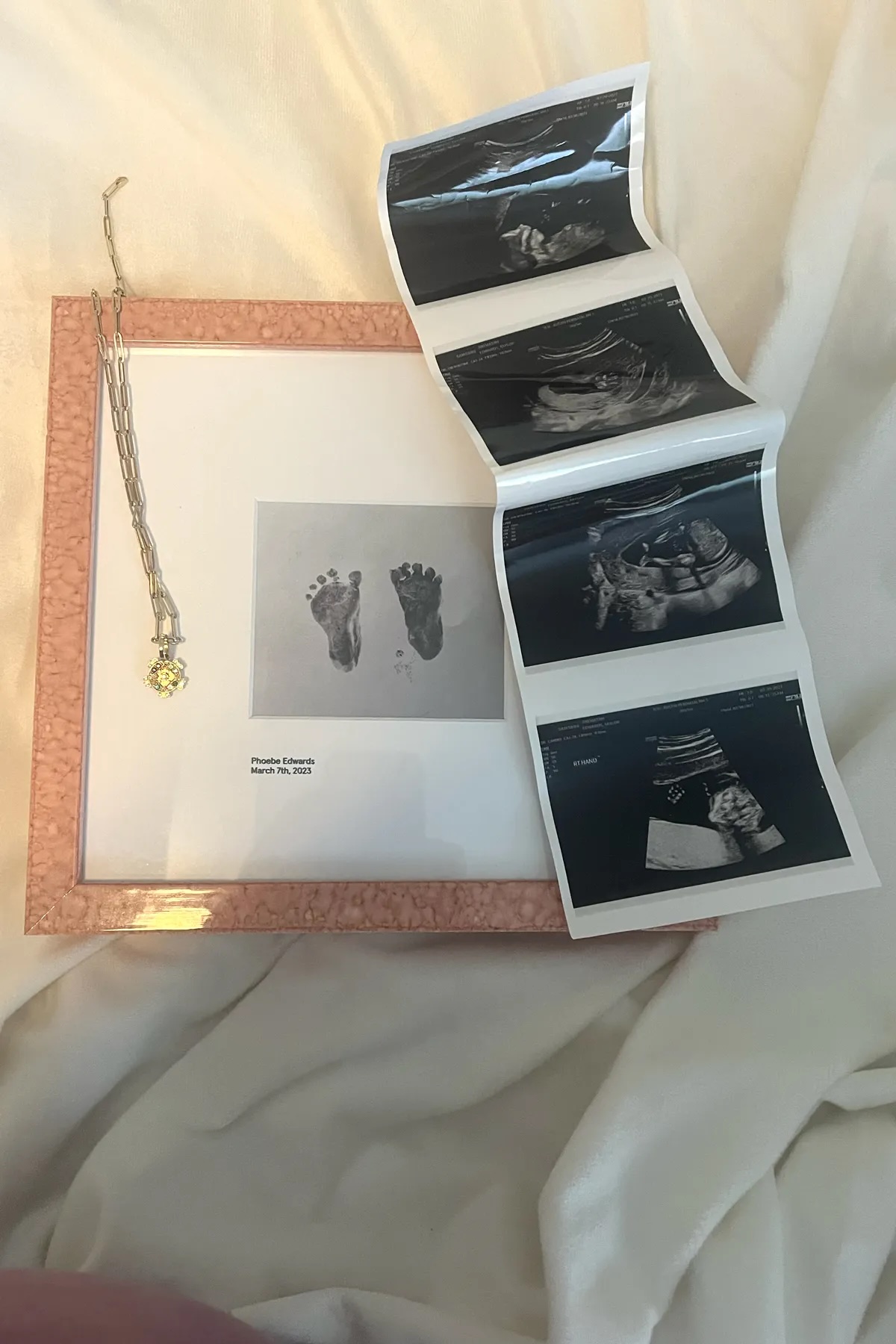

The doctor explained that their baby, whom they had named Phoebe, had a rare neural tube defect called encephalocele, in which her brain was growing out of an opening in her skull—a condition that was, in her case, determined to be fatal.

The news was “earth-shattering,” says Edwards, one of several women who are sharing stories with the organization Abortion in America about how their lives have been affected by abortion bans. “It felt like there was a gaping hole in the earth that just split open.”

What came next, she says, “added trauma onto an already traumatic situation.”

Edwards’ doctors outlined three scenarios: “I could go in their office weekly and get scans, and we would wait for her to die in utero. Or I could carry to term, which they thought was unlikely given her state,” she says. “If I did give birth, she would suffocate to death in front of me. Or I could terminate my pregnancy.” But, they told her, at 17 weeks, she couldn’t do so in Texas.

Less than a year earlier, after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling that guaranted a federal constitutional right to an abortion, Texas had enacted a restrictive abortion law that banned the procedure after six weeks of pregnancy.

While the Texas state law includes an exception for conditions deemed life-threatening for the mother, doctors told Edwards that it wasn’t an option in her case.

“I was terrified. I had worked so hard to become pregnant. My first experience of labor and delivery couldn’t be death. I couldn’t do that,” says Edwards, who added that continuing the pregnancy also meant an increased risk of sepsis. “I just knew I wouldn’t be able to get through it.”

With her petite 5’4” frame, Edwards was already showing, and the idea of carrying on with a doomed pregnancy seemed unthinkable: “I knew in my gut that we were going to terminate.”

Her doctor had handed her a piece of paper with the name of a New Mexico clinic that performed abortions, but Edwards was in a race against time because few clinics can do the procedure after 18 weeks of pregnancy. She called and got an appointment a week later.

She booked flights and a hotel on her card, nervous to have her husband connected with any of the arrangements for fear of the state’s “bounty law,” which allows people to sue anyone deemed to be helping someone get an illegal abortion. In crossing state lines, Edwards knew she wasn’t doing anything illegal—she’d even consulted with an attorney first—but she couldn’t shake her worry. “I did it out of fear, because I wanted to protect him as much as possible.”

On the morning she and her husband were to leave for New Mexico, she got a call saying the clinic had to cancel because they had a shortage of medication. They scrambled to find an alternative.

She canceled her hotel and flights and was able to find a clinic outside Denver that could take her. Her procedure was scheduled for March 7, 2023—when she was 19 weeks and 2 days pregnant. During the additional week’s wait, Edwards became ill with vomiting, dizziness and elevated blood pressure. Looking back, she believes the sickness may have been early preeclampsia symptoms; she had severe preeclampsia during her second pregnancy.

Because of the two-week delay in accessing the abortion, it had to be a more extensive, two-day procedure. And with each passing day, Taylor’s anxiety increased.

“The entire time we were in Colorado, when we got on the plane, we checked in, I was like, ‘Do people know what we’re doing? Oh my God, do they know why we’re here?’ ” says Edwards, who later joined other women who were denied an abortion in Texas in a lawsuit against the state (the state supreme court upheld the Texas laws).

“I didn’t want to be in an airport 24 hours after losing my child and bleeding. Then I remember being so, so afraid of being arrested when we landed back in Texas, even though I knew what I was doing was not illegal.”

Edwards says the experience was “the hardest thing I’ve ever been through in my entire life”—made worse by the fact that she was so far from home when she went through it. When she did come home, “I would sit in what was supposed to be a nursery and hold ultrasound pictures and sob.”

Because of the more extensive procedure, “I had tremendous scarring in my uterus.” That set back the date when she and her husband could try IVF again. She had to undergo reconstructive surgery for her uterus before they were able to transfer another embryo.

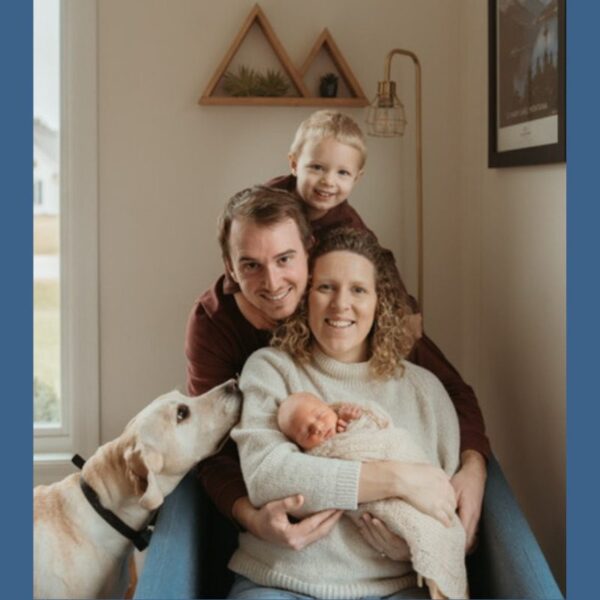

In March 2024, their son was born, with the help of IVF, and, Taylor believes, because she had a safe abortion. “A lot of people have to have abortions to become mothers. I know it’s an uncomfortable reality, but it’s just the truth,” Taylor says.

She’s endured condemnation and judgment for her decision, she says: “People think I don’t deserve to have my son because I had an abortion. But I have never, for one single second regretted my abortion. It allowed me to become a mother to a living child. It allowed me to preserve my fertility and my health.”

It took Taylor and Travis time to name their son—”I was so afraid that I was not going to bring him home,” she says.

The couple liked the sound of the names “Reid” and “Owen”, and then Travis realized if they named him Reid Owen Edwards, his initials would be R.O.E., a nod to the overturned 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that had decriminalized abortion.

“I was like, yep, that’s it,” Taylor says. “That’s a hundred percent his name. It was something that felt meaningful and that honored our daughter, too. It was a perfect fit.”

Wisconsin mom exposes painful reality of abortion laws after tragic pregnancy loss

For one Louisiana mom, speaking out about reproductive health care is a way of honoring her son’s memory