For birth workers and advocates Latona Giwa and Tasia Stewart, supporting pregnant people means embracing abortion care

Tasia Stewart is a birth doula who has worked with some of the most marginalized communities in New Orleans, including pregnant or parenting youth experiencing homelessness and survivors of sexual assault. Nearly two years to the day after Roe v. Wade was overturned, she joined her mentor, Latona Giwa, a birth worker and birth justice advocate, to talk about how their work has changed because of Louisiana’s abortion bans.

For both Tasia and Latona, their work is rooted in a fierce commitment to advocating for their patients. “It kind of started to be … a spiritual thing for me, helping mothers,” says Tasia of her early years as a doula. Both agree that abortion bans and restrictions in Louisiana are making it increasingly difficult for pregnant people to receive the care and support they need, creating harm that ripples out across entire communities.

Latona and Tasia’s conversation was recorded by StoryCorps Studios, part of Abortion in America’s collection of interviews with people in Louisiana about the ways in which the state’s abortion ban has affected their lives.

[F]rom the beginning it just felt kind of obvious to me that if we’re caring for pregnant people, abortion is going to be part of that care.

Audio Transcript

Tasia Stewart: So, I had this client. She had a lot of trauma from her family. She had been human trafficked also, and her coping mechanism at the time was drug abuse. She was just like, “I really don’t want to be pregnant. I feel like I wouldn’t be able to care for a baby.” And her question was, did she have any options?

As a doula in these moments, I feel like I’m put in a hard place, because I have to be that bearer of bad news to let them know there are no options for you. She ended up having to follow through with her pregnancy. We talked a lot. I would just let her call me and vent, but something inside of me just made me feel like her motherly instinct was not clicking on.

She started to have some complications with her pregnancy. They needed to monitor the baby and maybe even induce her earlier than her 37 weeks. When that happened, she got very afraid and she tried to flee the hospital. And I had to, like, convince her to go back. It made me very aware that she understands that she’s not ready for this and she really doesn’t have a way out at this moment.

The baby was born premature at, like, four pounds. And she bawled tears, crying to me like, “I just can’t do this. I’m not good enough to do this.” And I just tried to encourage her and tell her, like, “You are good enough. We’re here to support you and you’re going get through this.” She ended up going to a women’s shelter for moms with little babies and I didn’t hear from her for a few weeks.

And then I got a call one day, on the weekend. They told me that she had lost her baby. And they were like, “They think it’s SIDS”—Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Premature babies have a higher risk of SIDS. “But she fell asleep with the baby in the bed with her. And when she woke up, the baby was non-responsive.” So, that really hit me, because she was very in tune with who she was and knew what she can handle, but no one listened and she had no options.

Latona Giwa: That’s an extreme story with a really tragic outcome, but it’s not the only one. We chose this work to care for our clients, but we are being forced to make impossible decisions that might put our clients in danger, and there’s a ripple effect of that harm.

Tasia Stewart: Right. A lot of clients, they know where they are in life. They know what they’re capable of doing. And I really feel like they should have the right to say, “I don’t want to bring a life into this world, because I don’t feel like I’m capable enough to be responsible for another human being.” And I just think it’s very unfair that they don’t have that.

When their girlfriends needed abortion care, they showed up

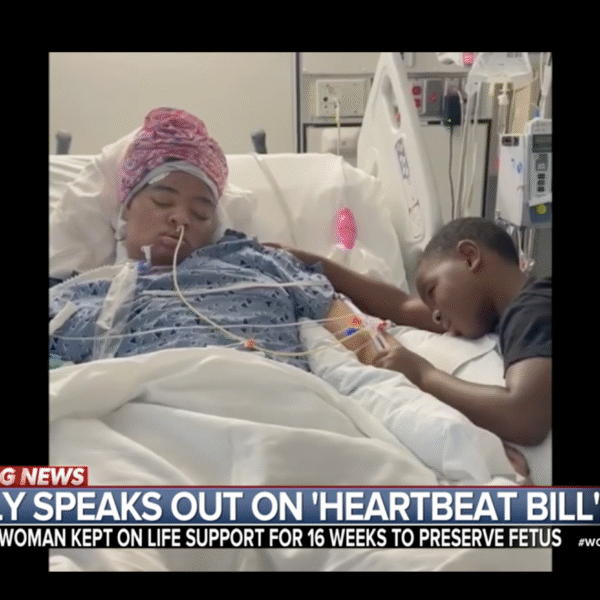

Mother whose daughter was kept on life support due to abortion ban speaks out