She wanted an abortion. Her only option was driving to Mexico.

Synopsis

This excerpt from “Undue Burden: Life and Death Decisions in a Post-Roe America” by The 19th’s Shefali Luthra looks at just how far away abortion can be in some parts of the country.

This is an excerpt from “Undue Burden: Life and Death Decisions in a Post-Roe America.”

Before Roe v. Wade fell, McAllen had been home to the last abortion clinic in Texas’s Rio Grande Valley, and Becky, a lifelong Texan and young college student, knew the place by sight. It was where the other girls at school used to go whenever they needed help, just by city hall, next to a church, and a short drive from an H-E-B supermarket. It was easy to find. There was a mural on the outside of brightly painted women standing in a field, holding what looked like balls of light, gazing up at the sun. The words hovered above them: “dignity.” “empowerment.”

Few places were harder hit by Roe’s fall than the Rio Grande Valley, which lies south of San Antonio and abuts the state’s border with Mexico. Even before 2021, reproductive health care in the region had been difficult to come by — and abortion, while technically available, was only barely so in practice. Minutes from the border, the clinic, a tiny Whole Woman’s Health outpost, had long been the only abortion provider for thousands of miles. In the fall of 2021, when the state’s six-week ban took effect, visits to the clinic fell precipitously, with the majority of Texans seeking abortions unable to make it there under that tight deadline. But abortions still happened. At least some people in the Valley were still able to get clinic-based care in the state, even if that meant driving for hours each way, testing themselves daily from the moment their periods seemed late. Even the $650 for an early abortion represented a tremendous expense; one woman recalled using some of the money she’d been saving to buy a home. People prayed to some higher power that they were still early enough in pregnancy to qualify.

After the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, though, even that sliver of an opportunity disappeared. Abortion in Texas was outlawed completely, and clinics like McAllen’s shut down. Farther north, Texans with means could conceivably drive to Kansas or New Mexico; they could book a flight to Colorado, California or New York. For a brief time, they could go to Florida or North Carolina. But in the Valley? The drive to any one of those states felt like an absurd proposition. The region’s southernmost cities, places like McAllen and Harlingen, were a good 12-hour drive from the closest New Mexico clinic, and Wichita was even farther. Flying out of the tiny local airport was an option in theory, but it meant having the money to pay for a plane ticket. In 2021, per U.S. Census data, the median household income in the area remained less than $50,000, about $20,000 below the national average and the lowest for major urban areas in the country. Scraping together the money for air travel was a luxury under the best of circumstances. And that was to say nothing of those who, regardless of the cost, simply could not safely leave the area. About 136,000 undocumented people lived in the Valley’s two largest counties. It was virtually impossible to drive north without hitting an immigration checkpoint, and without papers flying also wasn’t an option — not without risking deportation.

In the Valley, if you wanted an abortion, the options had already been limited. After Dobbs, they were virtually nonexistent. Local activists who worked in abortion rights — community organizers, abortion fund volunteers — frequently noted how ridiculous it seemed to suggest people travel north or west for an abortion. So many people who lived in this region had never left before; Albuquerque or Denver might as well be Mars.

Nobody had ever taught Becky about birth control. It never came up in school, and her parents, who had both emigrated from Mexico when they were young, didn’t tell her about the pill or even condoms. When her mom talked to her about pregnancy, it was in that looming, terrifying way. “You’d better not get pregnant,” she’d tell her. “If you do, you’ll have to raise the baby.” Neither of her parents believed in abortion, and Becky was hesitant to even broach the subject with them. Everything she knew, she’d learned from her friends and from whatever she could find online.

She’d had sex before, but now, at age 19, she had finally met her first ever real boyfriend. Luis was the first person she’d loved and the first she considered to be a true partner in every sense of the word. They’d talked about what they’d do if she got pregnant, even if only in the abstract. And for them the answer was clear: it had to be abortion. Becky lived with her parents, worked part-time at McDonald’s and was still a student at the nearby university. She knew she needed to finish school before she had a child; she’d promised herself forever that she wouldn’t become a mom until she was at least 20, though ideally a bit older. And she knew she didn’t have the money to feed another person. Her boyfriend, who lived with friends, didn’t even have parents to turn to for help. As for Becky, her mother, a school nurse, made as little as she did. Her father, whose immigration status was tenuous, earned even less.

Even adoption, often touted by abortion opponents, was something they wouldn’t consider. Becky’s boyfriend had entered the state’s foster care system when he was 9 years old, moving from family to family. Yes, he’d had food to eat and clothes on his back, but he’d never truly felt cared for by anyone who raised him, never received treatment for the asthma that had plagued him since childhood, and never really felt like he’d had a family that wanted him. It was an experience he still struggled to talk about, but it had instilled in Becky an unwavering belief: nobody should give birth to a child they weren’t prepared to raise themselves.

In that regard, she was different from her parents. Like them, she believed in God — but unlike them, she didn’t think that belief negated her right to get an abortion if she ever needed one. Her religion, she said, was the kind where you didn’t judge people for the choices they made about their own bodies.

Still, the day Becky’s pregnancy test came back positive, she couldn’t quite believe it. She’d been feeling sick for a few days, nursing a more painful version of the cramps and fatigue she usually associated with her period. Finally, at a baby shower for a friend, she snapped, leaving the party to pick up three pregnancy tests from a nearby store. Hiding in the bathroom at her friend’s home, she watched each test come back positive. Three double pink strips, three confirmations.

Becky didn’t trust any doctor to help her figure out how she might be able to terminate her pregnancy. She knew about the anti-abortion centers — the places that offered free if often inaccurate ultrasounds, along with diapers and parenting classes. In states like Texas, with abortion outlawed and clinics disappearing, pregnant people had started relying on those facilities, which largely aren’t regulated under the same standards as health clinics, at the very least to find out even roughly how far along they were and to learn what kinds of abortions they might be able to access in other states. But for Becky, who had no way of traveling north anyway, there was little point. And the risk of someone learning she was pregnant was too great. She had no idea whom they would tell or what lengths they’d take to make sure she kept it.

Weeks earlier, Becky had seen a post on Instagram from Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York touting the potential of misoprostol for people who no longer had access to legal abortion. The image came back to her now. If there was a way Becky could find misoprostol, and if she took enough on her own at home, she reasoned, maybe that could terminate her pregnancy. The fact that a government figure had recommended it — someone with far more authority or knowledge than she assumed any of her friends might have — gave her a shred of confidence. She learned that another friend, someone who had recently had an abortion, still had a few pills of misoprostol at home and was willing to share them. Becky picked up the two pills and prayed.

This was what it had come to: whisper networks and borrowing people’s leftover medicine, counting on someone to know a little more than you did, and hoping for good luck.

The Valley offered a picture of the future, a preview of what it looked like to live in a country where legal abortion simply wasn’t readily available.

Post-Dobbs, abortion rights organizers in communities like this one did what they could to help people access care. The Frontera Fund, an abortion fund serving the Valley, eventually started helping people leave the state for an abortion — if, of course, they could legally and safely travel for care, without worrying about immigration hurdles or the need to keep a trip secret. Another organization, South Texans for Reproductive Justice, pivoted from helping Texans access abortions to educating them on their options post-Dobbs, telling them which states still had legal abortion and what it would take to get there. They could steer them away from anti-abortion centers and distribute free Plan B pills to Texans hoping to avoid an unwanted pregnancy. And if people became pregnant, they could help them find medical clinics that offered affordable prenatal care, that might at least help them have as healthy a birth as possible.

All of this, they hoped, would help. But it could never be enough.

For people seeking abortion, it often felt like the only realistic option was to find someone who could help people get pills, from an organization like the European Aid Access or the Mexico-based Las Libres or from a friend who had extras. For those who had access to a car, and the freedom to leave the state, there was another option: scrounging up the cash, driving across the border to Mexico, and finding a pharmacy that might sell misoprostol. If you bought enough pills, and understood how to use them, that could do the trick.

Texans — especially those in the Valley, half of whom lacked health insurance — had been forced for years to treat health care as a luxury. As Nancy Cárdenas Peña , a local abortion rights activist, put it, “A lot of the conversations that people have here are either paying for their utility bill or going to their health care appointment.” The implications, too, were stark: Pregnancy-related deaths, on the rise across the country, had already been far more common in Texas compared with the national average. High-quality data are very difficult to come by, but a state report released in 2022 found that in 2019, the most recent year for which it had data, at least 118 Texas women died in part because of pregnancy; 72.7 people per 10,000 hospital-based deliveries suffered severe health complications. Texas, per one analysis, is home to 1 in 7 pregnancy-related deaths in the entire country, even though only 1 in 10 people lives there.

Once the Valley’s only abortion clinic had shut down, there were fewer reproductive health specialists in the area. Almost immediately after Senate Bill 8, Dr. Tony Ogburn, an ob-gyn at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley — the same university Becky attended — began to see colleagues leave the state because they knew they could no longer provide comprehensive reproductive health care in Texas. The pattern continued after Dobbs. He knew it wouldn’t stop — and that with each doctor who left, robust health care would get even more difficult to come by.

When Whole Woman’s Health left Texas, abortion rights organizers in the Valley thought for a moment they might be able to buy the building that had once housed the region’s only clinic. They could turn it into a center for reproductive health care, a place where people could learn how to access contraception and how to stay healthy if they found themselves pregnant. It would, they hoped, help people retain at least a modicum of control over their reproductive destinies, an act of resistance against their state’s new legal reality.

Instead, the clinic’s owners sold the building to an organization they believed to be a collection of doctors, but they would soon realize that they had been misled. The group that purchased the Valley’s last abortion clinic quickly sold the building to a local anti-abortion center. The transition — from a health care clinic staffed by actual doctors, where patients could learn about their medical options, to one owned by people who actively sought to deny people any reproductive choice — encapsulated within one building just what it meant to ban abortion.

When the leftover pills from Becky’s friend didn’t work, she remembered that she still had one other option. Born in the United States, she had the luxury of being able to drive across the border to Mexico — she made the trip every now and then, usually to go shopping at the flea markets. There, she knew, she might be able to find a pharmacy that would sell her more pills. If she took enough misoprostol, she reassured herself, she’d eventually be able to terminate her pregnancy. She’d heard from friends that pills would cost maybe $25, cheaper than an abortion clinic, but still money she didn’t exactly have to spare. Doing the math for the cost of the trip, she quickly realized that the only way to cover the cost would be to take on extra shifts at McDonald’s and hope that by the time she’d saved up enough money she wouldn’t be too late in her pregnancy for the medication to work. Every day that she waited, she grew increasingly nervous.

It was a trip many Texans had made before her, even before Roe fell; the border between Texas and Mexico is incredibly porous for those legally able to leave the country, and abortion pills in Mexico are far cheaper than the $650 or so that one might pay in a clinic. For some, it was a safer, more discreet option — you could pretend this was just a normal shopping trip, rather than risk being seen going in and out of the abortion clinic. Back then, though, it had still been somewhat of a choice, even if one option felt much more affordable than the other. You could go to Mexico, or, if you preferred, you could go to the health center in McAllen. You could get medications across the border, and, if for whatever reason they didn’t work, you could try getting pills or a surgical procedure at the clinic instead.

But if this trip didn’t work for Becky, she wouldn’t have any other options. There was no clinic she could go to — she’d have to keep the baby. The rest of her life, it felt like, was riding on whatever happened on this trip and how she made it through the days that followed.

The day she and her boyfriend crossed the border was another sticky summer morning, and Becky kept reminding herself how lucky she was to even make it this far. Abortion in Texas had been functionally outlawed for so long. She’d known other girls who hadn’t been able to get an abortion at the clinic and whose immigration status prevented them from safely leaving the country. There was one girl she kept remembering, a friend from school who wanted to wait a few more years before having a kid, but who was undocumented. She couldn’t go to Mexico for pills — even driving up north where she might pass an immigration checkpoint was far too risky. Instead, she’d had a baby at 17, even younger than Becky was now.

Once in Reynosa, the city on the other side of the border, Becky and her boyfriend went from pharmacy to pharmacy with a sense of purpose. They’d agreed to stick to areas well trafficked by tourists, hoping that there the odds were better of finding medication that was safe to use. Although generally the pills people got by crossing the border were safe, there were instances where people got the wrong kind, didn’t know how to take them properly, or, for whatever reason, found that the abortion didn’t work. Becky had never done something like this before—leaving the country to get health care or taking her reproductive health so directly into her own hands. Her Spanish wasn’t good enough to converse naturally with the men who worked at the pharmacy, some who sold misoprostol for well above the $25 she had brought with her. Those, she knew instinctively, must be tourist prices. The men were trying to overcharge her because it was obvious even to them how little she knew what she was doing and how desperate she was. Becky kept pulling out her phone, using internet translators to double-check the ingredients listed on the box and ensure it was in fact misoprostol. Still, a voice kept nagging at her. “If I get this wrong …” she worried. She couldn’t let herself complete the sentence.

Late in the day, they bought a 24-pack of pills. It was enough, she hoped, to terminate her pregnancy and to maybe keep a few extra in case a friend might need them in the future, paying it forward the way others had tried to do for her. From everything she’d found on the internet, she figured 10 to 12 pills would do the trick. She just hoped it wouldn’t be too much; she didn’t know if it was possible to overdose on the drug or what would happen if she took too many.

Becky had to wait another three days — her next scheduled time off from work — before she could take the pills. She waited until her parents had left the house, gagging slightly as she swallowed the medication. She wouldn’t tell even her brother what she had done. It wasn’t worth the risk of him telling her parents, which she knew he might if they ever got into a fight.

The aftereffects were just as miserable as she’d imagined. For the next two weeks, it felt like Becky couldn’t stop bleeding; she kept running out to the store to buy extra menstrual pads — more money she would have preferred not to spend — and hoping that eventually the blood would stop. In time, she kept telling herself, she’d know incontrovertibly that the medication had worked its magic. But the only proof she could count on was a negative pregnancy test.

It felt like such a big thing to hide, and she couldn’t always tell how well she was even keeping the secret. Only days after she took the pills, Becky’s mother began asking her when she’d go to the gynecologist — had she been tested recently for sexually transmitted infections? She really ought to go soon. Becky couldn’t tell if her mother suspected something, had noticed the blood, the pads, and Becky’s general fatigue over the past few weeks and put two and two together. But she wouldn’t risk asking her mother what she thought was going on. A week after taking her pills, Becky finally made a doctor’s appointment. By now, Becky hoped, the medication had done the trick — even if she was still bleeding, the doctor could mistake it for a period. If she was lucky, nobody would know she’d ever been pregnant. A part of her was still nervous that what she had done might somehow be against the law. Abortion was illegal in Texas, after all. If anyone found out she’d been pregnant, or figured out that she’d tried to get an abortion, would she go to jail? Or what about her boyfriend, who’d helped her cross the border and get the pills? What would happen to him?

It made sense she was afraid. Post-Dobbs, women like Becky represented a final frontier for the anti-abortion movement. They’d found a way to circumvent their states’ bans and to cling on to their own reproductive autonomy. Eventually, abortion opponents hoped to find a way to outlaw purchases like the one she had made. They just hadn’t yet figured out the best way to do it: whether they wanted to pass a new law, or whether they should attempt to prosecute people who self-managed their abortions under existing murder laws. The latter was something anti-abortion law enforcement officers had even attempted to do before Roewas overturned, typically targeting women of color, especially Black women and Latinas. It remains an open question how far the movement will go.

If the medication abortion had worked, it would take close to a month for Becky’s hormone levels to change, meaning that in the days and weeks after taking the medication a pregnancy test would still show up positive. When she went to the gynecologist, ostensibly just for STI testing, the doctor took one look at her bloodwork and scheduled a prenatal visit. She never mentioned abortion, never asked Becky if she wanted a baby. For weeks, Becky kept hoping that the doctor had been wrong, that the hormone levels were just residual. She couldn’t let herself think about the alternative.

At her first prenatal visit, Becky finally got the news she’d been waiting for: confirmation she was no longer pregnant. The doctor never asked any questions then, either. She just assumed that Becky must have experienced a miscarriage — she told her she was sorry.

Only while driving home from the doctor’s office did Becky at last let her relief show. At least for now, she could continue her life as a young woman in South Texas with no idea of what the future might hold for her, but with no constraints on what she could imagine. For now, she still had the freedom to decide for herself the life she wanted to live.

Excerpted from “Undue Burden: Life and Death Decisions in Post-Roe America” by Shefali Luthra.

Reprinted by Doubleday, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Shefali Luthra.

The 19th has a relationship with Bookshop.org. If you make a purchase through the Bookshop links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Western Wisconsin woman: ‘I am alive today because abortion saved my life’

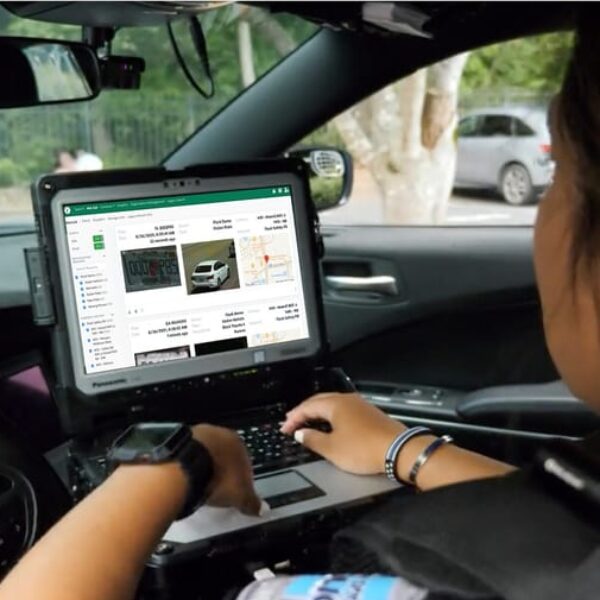

A Texas Cop Searched License Plate Cameras Nationwide for a Woman Who Got an Abortion