Texas’ restrictive abortion law sends Houston teen on cross-country odyssey for help

J broke down and wept inside the dingy CVS bathroom as she watched the second pink line begin to appear on her pregnancy test.

“I didn’t beat teen pregnancy,” the 17-year-old Houston high school student thought as waves of shock and fear swept through her mind that November afternoon.

As a Texas teenager, J had few options. She had no right under Texas law to end her pregnancy. Anyone who helped her get an abortion in the state could be charged with a felony and sent to prison for up to 99 years. The closest place for J to get an abortion was in New Mexico – 750 miles away. And her dad would be furious if he found out.

“There’s no hope,” she thought. “I’m just going to be a teen mom.”

J walked out of that CVS bathroom and embarked on a physically and emotionally taxing odyssey to try to end her pregnancy, one that would take her on a 1,500-mile, 48-hour, road trip to and from a tiny New Mexico abortion clinic willing to offer her the help she wanted. To tell J’s story, the Houston Landing agreed to protect her identity by using initials rather than full names.

Texas has become increasingly perilous for women and girls like J.

Since Texas imposed its strict abortion ban in 2021, a new analysis suggests, pregnant women have been dying in rapidly increasing numbers. A recent Johns Hopkins University study found that infants are far more likely to die in Texas than anywhere else in America. Houston has one the worst rates of premature births in America’s biggest cities.

Growing numbers of Texas doctors specializing in women’s health say they are looking to leave the state or retire early. Scores of doctors treating pregnant women say Texas abortion restrictions have had a fatal chilling effect on their ability to save lives when their patients face life-threatening pregnancies.

Texas is suing for the right to look at the medical records of women who leave the state to end their pregnancies. One Texas lawmaker is pushing a bill seeking to block women in Texas from even looking at websites about abortion pills. Five Texas counties have enacted legally questionable travel bans designed to prevent residents from leaving the state to end their pregnancies. And President-elect Donald Trump has raised the possibility that he could try to crack down even further on women’s ability to use abortion pills, a move that would make it harder for women to end their pregnancies.

Texas also has seen a rise in teen pregnancies since abortion was banned in the state, reversing a 15-year trend. The increase in 2022 was propelled by high rates among Hispanic teens like J.

“Texas continues to redefine how far we will go in pushing women back into the 19th Century,” said former state Sen. Wendy Davis, a senior advisor with Planned Parenthood Texas Votes, who herself had a child when she was 19 years old. “There are continued efforts to figure out ways to tighten the noose they have put around the necks of women of this state.”

Texas women lead the nation in leaving their state to end their pregnancies. More than 34,000 women left Texas in 2023 to get an abortion – more than doubling since 2019, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a nonpartisan reproductive rights research and policy group. Most go to the neighboring states of New Mexico or Kansas, which have more lenient abortion laws.

Before abortion was banned in Texas, about 50,000 women had abortions in the state in 2021, according to data from the Texas Health and Human Services Commission. More than 14,000 – nearly a third – came from Harris County.

Houston women seeking to end their pregnancies now face some of the worst geographic challenges in the state.

Seeking options

J had a feeling she might be pregnant ever since the condom had slipped off during sex with her boyfriend. The November test in the CVS bathroom confirmed her worst fears.

She talked it over with her boyfriend. They agreed: Neither of them was ready to take care of a child. They agreed on ending the pregnancy. But how?

One of J’s friends gave her a recipe for a tea she was supposed to drink until she had a miscarriage. J was wary. Another friend suggested she defy Texas law and mail-order abortion pills. That sounded dodgy to J. So she turned to her older sister, a health care worker who might be able to help.

L told her younger sister she would support whatever decision she made. She was relieved when J told her she didn’t want to have a baby.

“She’s so young,” L said. “She’s applying to colleges and I wanted to make sure to give her that chance. But I did tell her not to do this again – because we cannot be doing this again.”

The best option they could find was a tiny New Mexico abortion clinic on the outskirts of El Paso intentionally set up to help pregnant Texas women. It was the best, closest place they could find that wouldn’t require the teenager to tell her dad and get his support before getting an abortion.

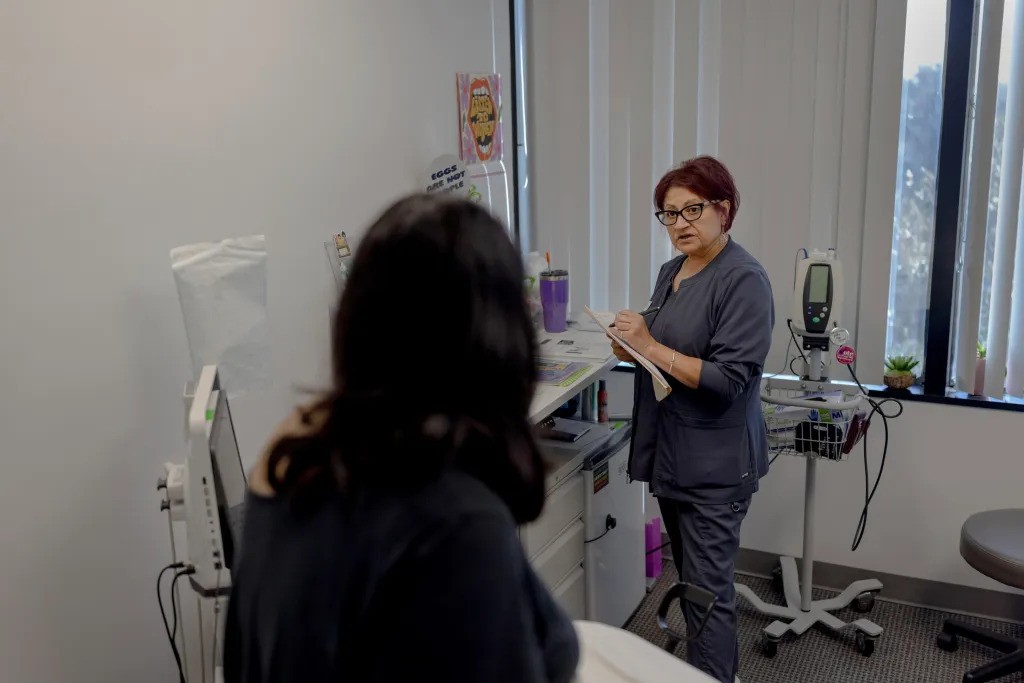

J battled nausea and fatigue in early November when she went to get her first ultrasound at Houston Women’s Reproductive Services, a once-expansive abortion clinic that has shrunk into a three-person health center in a nondescript high-rise in northwest Houston.

“It’s completely unfair,” J said after getting confirmation that she was about five weeks pregnant. “It’s absolutely disgusting that we have to travel to another state just because we don’t want to give birth to a whole other living being. So many women have given up on their dreams because they are forced to have a baby.”

J didn’t want to give up on her plans to go to college. She could count on a secretive network of nonprofits supporting abortion rights to cover part of her costs, but not much.

“It’s going to be very expensive because we are a low-income family,” she said.

Kathy Kleinfeld, founder of Houston Women’s Reproductive Services, and the nonprofit Lilith Fund, provided J with a free ultrasound as she weighed her options.

“It just infuriates me that people have to go through so much to access care and I know many don’t have the resources or abilities to jump over all these hurdles,” Kleinfeld said.

Heading to New Mexico

After L got off work and J got out of school on the third Friday in November, they climbed into a car for an 11-hour, 750-mile drive through the night to Santa Teresa, New Mexico.

J fought the urge to throw up in the backseat as she drank Gatorade and listened to a mix of Disney Princess tunes on her headphones. She slept fitfully through the Saturday morning sunrise as they closed in on El Paso and crossed into New Mexico. They drove past the Women’s Reproductive Clinic of New Mexico before it opened and saw a trio of jittery anti-abortion activists with pamphlets and a purple sign: “Change of heart? Abortion Reversal Solution Text or call 915-”

After decades battling anti-abortion activists in Texas, Dr. Franz Theard opened the New Mexico clinic in 2005. Theard became something of a folk hero in the abortion rights movement for his unflinching stand on the issue amid the death threats that led to a brick being thrown through a window at his El Paso home and anti-abortion protesters scattering the remains of aborted fetuses around his clinic.

Gabi Theard was five years old when the brick came smashing through her El Paso bedroom window. It is the first memory she has of understanding what her dad was doing for abortion rights in America. But Theard had her eyes set on something else for her life. She moved from El Paso to Austin, where she jumped into marketing before turning her full-time focus to being a DJ in the city’s competitive house music scene.

Theard’s DJ alter ego was Max Manila, a.k.a. the “Queen of Native Hostel.” For three years, she was the featured DJ at a popular house music residency in an Austin nightclub. Then came the 2022 U.S. Supreme Court decision that overturned Roe v. Wade. Texas quickly outlawed abortion. Theard’s father shut down his El Paso clinic for good and shifted his base of operations to his center in New Mexico, which was strategically located a few minutes from El Paso.

DJing in Austin lost its appeal for Gabi. She moved back to join forces with her dad to keep the New Mexico clinic open.

“Texas is not a safe place to be a pregnant person right now,” Theard said. “I think it’s the most dangerous state to be a pregnant person.”

New Mexico’s permissive abortion laws have made it a go-to state for Texas women seeking to end their pregnancies. Between 2020 and 2023, abortions in New Mexico rose by 220 percent, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

Patient No. 9

J and L parked the car on the other side of a boxy strip mall – away from the watchful eye of any anti-abortion protesters who might write down their license plate and track down the owner. They both pulled their sweatshirt hoods over their heads and walked into the clinic as anti-abortion activists silently looked on.

“You’ll be identified as ‘Patient No. 9,’” the clinic receptionist told J. “We don’t use names here for privacy.”

The clinic is tucked away in the back of the strip-mall, next to the Garden of Dreams, a mom-and-pop marijuana shop featuring a mural of two marijuana leaves topped by a halo and a red-eyed rabbit smoking a joint.

J and her sister sat in the narrow, five-chair reception area with ziplock bags of Ritz crackers (for patients with nausea) sitting in a basket next to actress Jenna Ortega on the cover of Vanity Fair. Gigi Theard came out to usher the sisters back to her office.

J, with her hood still over her head, sat down in a chair in front of Theard’s white desk.

The consultation took less than 10 minutes. Theard walked J through the process: An ultrasound to make sure she could take the pills. Putting one mifepristone pill in her cheek and letting it dissolve so the medicine could stop the fetus from growing. Then taking four misoprostol pills the following day to trigger the miscarriage. The visit cost about $600.

Theard assured J that her visit to New Mexico would remain confidential. Even if she had to go to a Houston hospital if she was worried about too much bleeding, the doctors would never be able to tell that she had a medically induced abortion. She could just tell them she was having a miscarriage, reducing her risk of being investigated for having an abortion.

“Everything you do here, stays here,” Theard told J. “If you need the E.R. I do not want you to worry. They will not know that you have taken the medication. It is identical to a miscarriage. No one can argue. It’s not a lie.”

After taking the first pill, J pulled her hood tighter as she and her sister headed out of the clinic, past the protesters on the other side of the parking lot.

“How are you?,” they shouted as the sisters walked to their car. “We are here to talk if you need anything. You can change your mind!”

The sisters checked into an El Paso hotel and collapsed. J battled more nausea and fatigue as she waited to take the second round of pills. Taking the pills in Texas would put L at risk of being charged as a felon for helping her sister end her pregnancy.

Early the next morning, the sisters made the long drive back to Houston, where J was overwhelmed by crippling cramps and waves of nausea. She stayed home from school and called her sister after throwing up in her room.

“I felt like I was going to die,” she said later.

The two sisters worried they would have to go to the emergency room, which would mean their father would find out. They called the clinics in Houston and New Mexico for advice. The staff assured them the symptoms were normal – and a sign they were working.

Back on track

The Friday after Thanksgiving, the sisters returned to the Houston clinic to see if the medications had done their job. J wore sweatpants and furry slippers. The office was peppered with small empowering touches – purple roses set in the waiting room next to a sign reading, “I want every girl to know that her voice can change the world,” and a poster of the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg with a quote from the feminist icon “Women belong in places where decisions are being made.”

J slipped into the exam room and into the medical gown. Glenda Lima, the sonographer, checked in with J before doing the exam. J lay back on the table and waited anxiously for the ultrasound.

“There is no longer an active pregnancy,” Glenda told her.

J made a fist and pumped it by her side: “Yesss…” she whispered.

She walked out of the examination and gave her sister the news. The two exchanged high fives.

“I felt trapped,” J said after the exam. “I was scared because I didn’t know if it was going to work out well. Now, I just have to get back on track.”

Joe Pojman, executive director of the Texas Alliance for Life, called J’s situation “heartbreaking” and said he wished that her sister had guided the teenager to one of the dozens of state-funded crisis pregnancy centers in Houston.

“I wish the sister would have helped her sibling find an agency in Houston to help her give birth to the child,” Pojman said. “It’s a tragedy that this woman would want to go to extreme lengths to end her pregnancy rather than go to one of these centers that is probably within 10 miles of where she lives so she could successfully carry the child, give birth, and give them up for adoption if that’s her decision.”

J called Pojman’s view “inconsiderate and ignorant.”

“It’s my body and they don’t have to give birth to it or carry it for nine months,” she said. “The adoption systems are horrible and I wouldn’t want to have a baby if I knew I was just going to leave it.”

John Seago, president of Texas Right to Life, said there was a very small chance anyone would try to send L to jail for helping her sister. Instead, Seago said, groups like his are looking to work with the Texas Legislature next year to find ways to target clinics like the one in New Mexico.

“Just because the abortions started in another state and ended here in Texas, that doesn’t erase their criminality,” he said.

Kleinfeld gave the sisters hugs before they headed home.

“I’m so glad you are on the other side of this,” she told J.

The sisters smiled and held hands as they skipped down the hallway to the elevator, heading out to their car and off to wait anxiously for emails from college admissions offices that might offer J some good news.

Houston Landing Photographer Lexi Parra contributed to this story.

What one NICU nurse wants you to know about how abortion bans affect babies in Texas

In her own words: Why this Texas physician now helps women in Virginia